Good morning. The Fed is worried about China all of a sudden. Welcome to the party, guys! If you are worried, too, or if you aren’t, email me at robert.armstrong@ft.com, or Ethan at ethan.wu@ft.com.

A big red flag

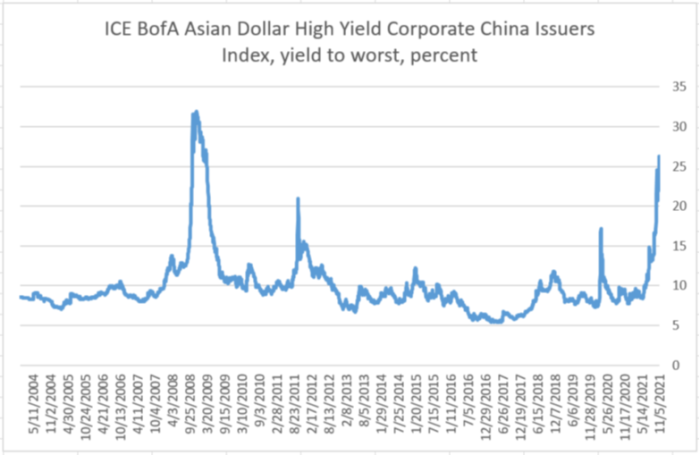

I was astonished by this article in The Wall Street Journal yesterday morning, pointing out that Chinese junk bond yields are now above 25 per cent (I was a bit embarrassed, too; this is something I should have noticed without the WSJ having to tell me about it). Here’s a chart of an index of junk-rated, dollar-denominated Chinese corporate bonds going back to 2004 (data from Bloomberg):

What this chart suggests to me is pretty simple: it is somewhere between very hard and impossible for a junk-rated Chinese company to refinance its debt. And that means bankruptcies. It’s not just property developer Evergrande that is going to miss payments. From the WSJ piece and quoting Jenny Zeng, co-head of Asia Pacific fixed income at AllianceBernstein:

Market sentiment is still very weak. The key question is, who has sufficient liquidity to muddle through this?

Some more bad news. Bloomberg has reported that at least one investment grade Chinese company is also getting kicked in the teeth:

Sino Ocean Group Holding Limited, part-owned by the finance ministry, has become the latest property company to see its bonds slump. Its 4.75 per cent note due 2030 fell on Monday to as low as 73.48 cents on the dollar, with spreads over comparable Treasuries widening to a record 800bp, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That’s despite the firm being rated investment-grade at two global credit assessors and holding about 54 times more cash and equivalents than China Evergrande Group. Sino Ocean’s shares have been doing better, rebounding 35 per cent from their September low. They rose 3.5 per cent on Monday.

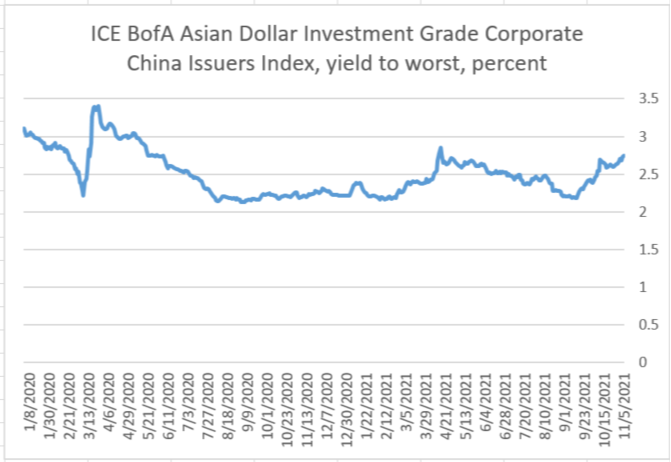

So far, Sino Ocean seems to be an isolated case. The panic in junk bonds does not seem to be hitting yields in investment-grade Chinese debt, which are rising, but at a more stately pace. Here is the investment grade equivalent to the bond index shown above, just since the start of 2020:

China’s stock market doesn’t seem bothered, either; it has been trading sideways since July.

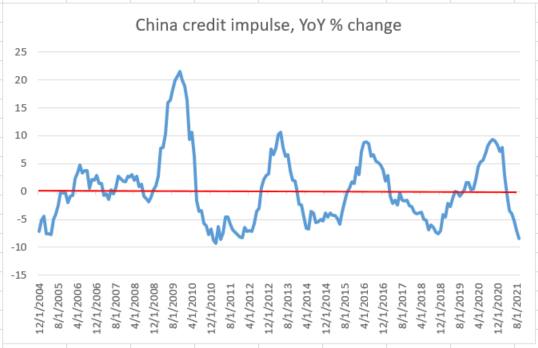

I really have no idea whether or not China is headed for a broader market crackup, or if instead the problems will be confined to high yield debt, where real estate plays such a big role. But perhaps the biggest question is how much carnage the central government is willing to tolerate before it eases credit conditions. So far, the policy has been tough love. Here is the famous “China credit impulse” chart, which shows annual per cent change in the contribution of new debt to China’s gross domestic product (Bloomberg data again):

The credit spigots have most emphatically not been turned on. This has been the case at least in part because China has had the luxury of importing the demand created by government stimulus in the US and elsewhere. But with its economy slowing down, how long can the government wait? As one longtime China analyst said to me:

The contribution of the property sector to GDP growth is just too important to ignore, and with the regular resurgences of Covid closing down the country every few weeks, not to mention what promises to be a cold winter, I just don’t think [Beijing has] the stomach to keep the property sector down.

To be clear, we are not talking about bailouts of investors in dollar-denominated bonds here. But reserve requirements and mortgage rules could be loosened, for example. In any case, significant Chinese stimulus would be a big deal for global markets, especially in areas such as commodities.

SoftBank’s buybacks beat the alternatives

Masayoshi Son, chief executive and largest shareholder in SoftBank, says that net asset value is the “most important indicator” of the company’s progress. Everyone knows this is wrong. What matters most for SoftBank is closing the gap between its NAV and its share price, which now stands at over 50 per cent.

Is a buyback the best way to close the gap? On Monday the company announced it would buy back $8.8bn more of its own shares, the second big authorisation, after the $23bn buyback that started in March 2020 and was completed in May.

Now, assuming SoftBank marks its assets realistically, and the gap is as big as it appears, the best thing would be to break up the company. But Son does not want that, and he owns 27 per cent of the shares, so that is off the table.

The buyback is the next-best option, for two reasons. One, cash spent on a buyback is cash that Son can’t spend on another moonshot idea that would make SoftBank even messier and widen the discount further. His adventures in WeWork and investing in call options on tech stocks show he can no longer to be trusted with other people’s money. The top priority is forcing Son to stop setting money on fire. The buyback takes the matches away.

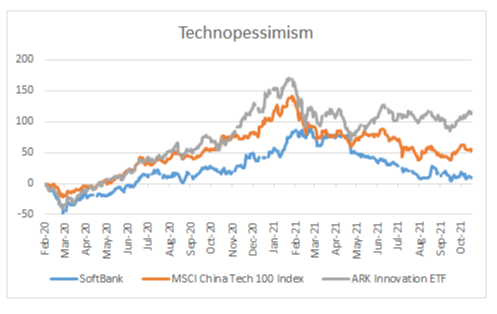

Second, the stock is cheap now. Buying them back provides exposure to a rebound in valuation, as well as any tightening of the NAV discount. The recent slump in SoftBank’s shares is not just down to the company’s foibles. It reflects the fall in the price of Chinese tech stocks, as well as a general loss in appetite for tech long shots. Here are SoftBank’s returns plotted against Cathie Wood’s ARK tech ETF and an index of Chinese tech groups:

And here is SoftBank’s price/book ratio:

The buyback is undoubtedly a long shot. China tech may not come back, investors’ speculative appetite for tech start-ups might not come back, and SoftBank’s NAV gap may never close. But the returns on the buyback, should any of those things happen, will be very good — on a risk-adjusted basis, much higher than anything else Son is likely to do. And his authorisation of the buybacks shows that, at some level, he admits that. This is dreary, but it’s progress.

One good read

From The New York Times: Americans think the US economy is worse than it is (I think it is all down to petrol prices, but it may be a little more complicated than that).