Managers of bonds backed by pools of risky loans to indebted companies are rushing to get deals done before the Libor interest rate benchmark underpinning the market begins to fade away next year.

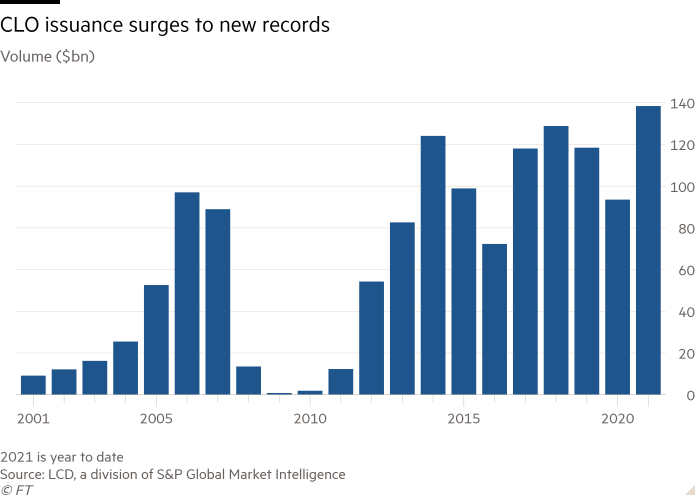

Issuance of collateralised loan obligations, which take bundles of leveraged loans and use them to back payments on chunks of new debt, has soared to a new record this year, according to data from LCD, a division of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Total issuance in 2021 reached $140bn this month, already surpassing the previous full-year record of just under $130bn set in 2018. August and September marked the heaviest issuance months for CLOs on record.

The frenetic pace of new deals comes as the industry readies itself for the transition away from Libor, the disgraced interest rate benchmark at the heart of global finance that was found to have been rigged by bankers a decade ago. From next year, new CLOs will have to be pegged to a new interest rate benchmark, with managers, investors and bankers still working out exactly how that will work.

“Many managers and investors are trying to get deals done now,” said Ujjaval Desai, head of structured products investing at Sound Point Capital Management CLO businesses. “When we look at our pipeline it would be better to get deals done sooner rather than later and not have to worry about the January effect. That’s what’s driving things right now.”

Regulators have mandated an end of year deadline for US dollar Libor to stop being used in new deals, with CLOs issued before that deadline able to continue being pegged to Libor until a hard stop in the middle of 2023.

Other managers and some analysts are quick to point out this is not the only reason for the boom in CLO issuance.

As inflation pressures mount and the Federal Reserve prepares to withdraw some of its crisis-era support for financial markets, interest rates — reflected in the level of Libor or in other benchmarks like Treasury yields — have begun to rise. That has resulted in rekindled demand for floating-rate investments like CLOs whose interest payments rise and fall with benchmark rates, insulating investors from the prospect of interest rates moving even higher still.

Companies have binged on cheap loans through the Covid crisis, which has provided a big source of debt to package up in to CLOs. These instruments are the biggest buyers of leveraged loans, helping companies borrow record amounts of cash this year, with those new loans serving as collateral for new CLO deals.

Nonetheless, the looming Libor deadline has added a further sense of urgency in the market.

“Anecdotally we have seen that a lot of managers are looking to get one more Libor indexed transaction done this year ahead of the Libor transition next year,” said Steve Anderberg, in charge of rating new CLOs at S&P Global.

Some managers say that economically, there is little incentive to wean themselves off Libor early.

From January, new CLO deals will most likely be pegged to Sofr, a new benchmark that differs from Libor because it is based on actual transactions in the repo market, whereas Libor was easier to manipulate because it was based on bank submissions.

However, most of the loans available for CLO managers to buy and put in to new deals will still be pegged to Libor. Only a couple of Sofr-based loans has been issued so far, with a few more in the works.

This introduces a new mismatch for CLO managers to contend with. Bankers say most loans are currently priced off one-month Libor, which is currently 0.09 per cent, whereas tranches of CLOs bought by investors are likely to be priced over Sofr at 0.05 per cent.

To try to erase this difference, the Alternative Reference Rates Committee, an industry group formed in 2014 by the Federal Reserve to oversee the Libor transition, has come up with pre-set “spreads” — essentially an additional amount of interest — to be added to the level of Sofr.

But even these are meeting with disagreement among market participants. The additional interest recommended by Arrc to be added for a three-month period — typical for CLO debt — is 0.26 per cent, which would take Sofr to 0.31 per cent, increasing CLO managers’ interest costs to investors from the current level of three-month Libor at just over 0.12 per cent.

Managers argue this spread should be lower to match Libor, or the additional fixed yield paid to investors above the benchmark should reduce to account for the difference.

It sets up a period of negotiation with investors, as wrinkles in the patchwork of rates being sewn together are ironed out.

“The cost of capital for the manager should be the same,” said Robert Zable, a senior US CLO portfolio manager in Blackstone’s credit arm. “How it happens will depend on market forces.”