The UK’s largest energy suppliers are requesting a multibillion-pound emergency support package from the government to help them survive the crisis sparked by high gas prices, including the creation of a “bad bank” to absorb potentially unprofitable customers from failing rivals.

Kwasi Kwarteng, UK business and energy secretary, is holding emergency talks with regulator Ofgem on Sunday and is due to meet energy suppliers face-to-face on Monday, amid fears that dozens of smaller challenger companies could go bust in the coming weeks due to record wholesale costs of natural gas and electricity.

People familiar with the weekend talks say the largest energy suppliers are asking the government for substantial support to handle potentially millions of customers from failing companies and may require the creation of a “Northern Rock-style bad bank” to house customers they could not take on without losing money.

While no decision has yet been taken, the proposals to the government reveal the scale of support the industry believes will be required to avoid causing long-term damage to the sector should a large number of energy suppliers fail in the coming weeks.

Kwarteng is said to be examining the proposals and has accepted that significant intervention may be necessary, fearing the existing contingency plans may not be sufficient. Allies said he was looking at “Plans C, D and others”.

“We need a lot of contingency plans in place,” said one ally of the business secretary.

Most existing household energy tariffs are not enough to cover the cost of supplying new customers, making large energy companies extremely reluctant to take them on without government support, potentially including state-backed loans or other measures.

Talks with the government had focused on three different approaches, four people familiar with the situation confirmed, while stressing that ministers were “keen not to reward failure”.

One suggestion is for the formation of a “bad bank” which would take on unprofitable customers from failed suppliers — a move reminiscent of measures taken at the peak of the financial crisis in 2008 and one designed to avoid weakening otherwise strong companies.

“This could get the industry through the current period of crisis,” one person familiar with the talks said.

“By parking the problem in a bad bank, it would make it easier to sort out the immediate crisis and then take stock longer term. It would allow the government to handle several suppliers going bust at the same time.”

A second person, however, cautioned that such an approach could be difficult to manage in practice, especially given that suppliers all run on different operating systems. There would also be a question of whether Ofgem would take responsibility for customer care and handling complaints.

Another option would see the government underwrite debt for the larger suppliers, if they were to incur losses by taking on customers.

A third route would see Ofgem stepping in and, instead of shifting the customers of the failed suppliers to another provider, would administer the company through the immediate crisis, effectively leading to its nationalisation, with the government on the hook for any losses.

Two people familiar with the talks said the cost of the eventual package could run to billions of pounds for the government given the number of companies that are expected to fold in the coming weeks.

Five smaller suppliers have already gone out of business since the start of August as surging wholesale prices have left companies with insufficient hedging strategies or weak balance sheets unable to cover the cost of the energy they had committed to supply.

There are growing concerns among chief executives of the bigger suppliers that the five, including People’s Energy and Utility Point, with 570,000 domestic customers between them, are just the tip of the iceberg. Further failures in the next seven to 10 days could see 1m customers needing to be transferred to new suppliers.

The business secretary has been warned by the industry that out of 55 companies in the sector, only between six and 10 could be left standing by the end of the year.

Energy company executives say each customer they absorb under Ofgem’s “supplier of last resort” system could lose them hundreds of pounds a year, making it unfeasible to take on millions of customers should the worst fears about the number of failures in the industry pan out.

The cost of buying enough wholesale gas and electricity in the spot market to supply an average household is estimated at about £1,600 a year, while the Ofgem-set price cap on energy bills is at present £1,277, having already been raised by £139 last month.

Energy suppliers have said they are effectively subsidising customers at current price levels.

Octopus Energy, one of the fastest growing energy providers in the UK — which is now considered a large supplier — said on Sunday that a number “of less prudently run or less well-backed suppliers have folded with rising gas prices and some more are expected to follow”. It has joined other companies, including Eon, in calling for the government to move environmental levies from electricity bills to help lower customer bills.

While energy supplies for existing customers have largely been hedged in the futures market by the largest energy companies, allowing them to remain profitable, this is not possible in relation to new customers as they have not been able to plan ahead for how much gas and electricity they will need to buy from the wholesale market.

“Energy suppliers have already provided hundreds of millions of pounds in financial assistance since the start of the pandemic,” said Emma Pinchbeck, chief executive of industry body Energy UK.

“The industry will continue that support this winter, during what is an extremely challenging time for the sector itself — as has been shown by more suppliers exiting the market this week.”

The gas crisis has reverberated across UK industry including threatening food supplies. The meat industry is facing an acute shortage of carbon dioxide after surging gas prices prompted CF Industries, a US company, to suspend production at two large UK fertiliser plants last week.

Kwarteng met CF Industries boss Tony Will on Sunday to discuss options for restarting production at the plants in Cheshire and Teesside, including the possibility of government financial support to avoid exacerbating the supply-chain crisis.

CO2 is a byproduct of fertiliser production, but it is currently uneconomic for CF to make it. Kwarteng will on Monday discuss with cabinet colleagues a temporary financial package to reopen the plants, to help resume production of fertiliser and CO2.

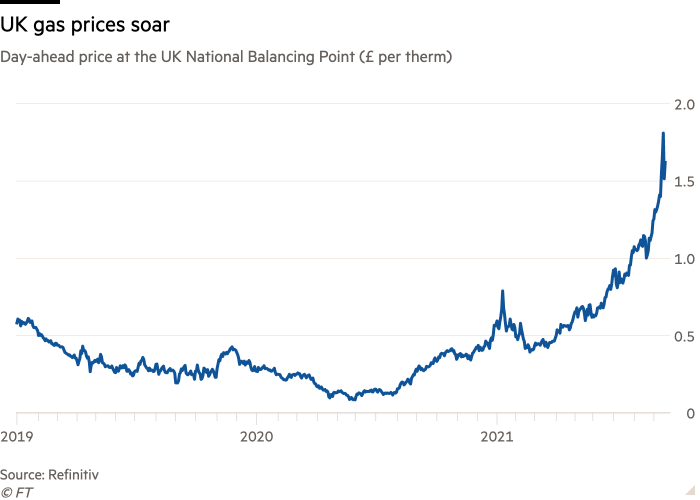

Gas prices in Britain and Europe have hit repeated highs in recent weeks as traders fear the continent is heading into winter with low stocks following lower supplies from Russia as well as domestic sources as gasfield operators undertake maintenance delayed from last year.

Kwarteng said in a series of tweets on Sunday that it was possible a “special administrator” would be appointed at companies where finding a supplier of last resort “was not possible”. “The objective is to continue supply to customers until the company can be rescued or customers moved to new suppliers,” he added.

But the business secretary is said by colleagues to be worried about the impact of the crisis on consumers and also on future competition, if the fallout from the shock sees a return to a more concentrated market, once again dominated by big players.