A clash erupted between two of the world’s most prominent investors this week, reflecting a widening divide on Wall Street about the viability of putting money to work in China.

Fund managers have been cooling on the world’s second-largest economy since president Xi Jinping launched a volley of regulatory stings against sectors ranging from education to video games over the past 10 months. The moves have wiped almost half the value off of a Goldman Sachs basket of US-listed Chinese stocks from a peak early in 2021 and halted the once vibrant flow of Chinese companies listing in New York.

But this week threw the disagreement into the open when BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, announced on Wednesday it had raised $1bn for its first mutual fund in China, seduced by the chance to tap into the country’s growing savings market. Just a day earlier, billionaire financier George Soros wrote in the Wall Street Journal that BlackRock’s move into China was a “tragic mistake”.

“BlackRock’s wrong,” the famously outspoken 91-year-old former hedge fund manager said, having previously warned that investors in China face “a rude awakening” because “Xi regards all Chinese companies as instruments of a one-party state”.

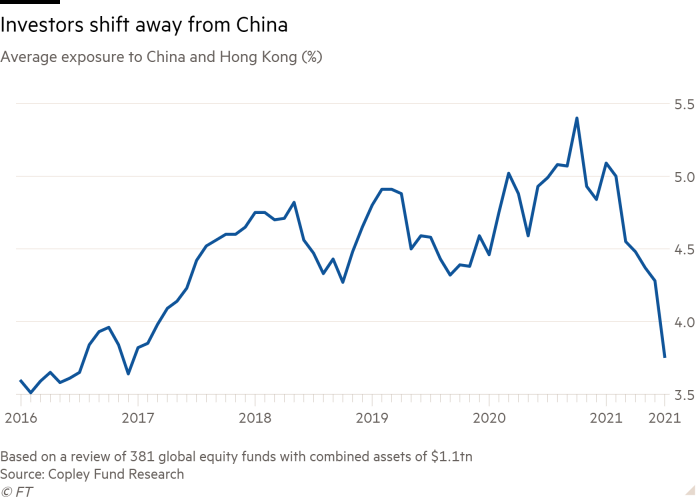

Managers running active global equity funds have chopped their allocations to China and Hong Kong to the lowest level in four years, according to Copley Fund research, a data provider. Looking at a sample of 381 funds with more than $1tn in assets, Copley calculated that just over a quarter now hold more Chinese and Hong Kong stocks than the benchmark global index. In early 2015, a peak of 45 per cent of investors held such outsized bets on China.

“You don’t know what Chinese companies are being run for — profits or the government,” said one London-based hedge fund manager. “There is no rule of law. Avoid China — or be an insider.”

Cathie Wood, the chief executive of Ark Invest and one of the most closely watched investors, told an audience of institutional fund managers on Thursday that her fund has “dramatically” slashed its exposure to China since late last year.

Chinese authorities were now focusing on social issues and social engineering at the expense of capital markets, she said. Now, her portfolio contains stocks from the country only if the companies are “currying favour” with Beijing.

Foreign investor jitters reflect a 10-month period in China that has been marked by a series of sudden offensives by Xi in the business and economic sphere. These unexpectedly harsh interventions have created a sense of unpredictability that some investors and analysts have said could make the country’s vast markets effectively uninvestable.

Almost no sector has remained untouched by the Communist party’s “common prosperity” campaign, which has included a crackdown on China’s biggest tech companies and on real estate speculation, strict limits on the amount of time young people are allowed to play video games, and a ban on the for-profit education sector.

Chinese authorities have also indicated they might clamp down on so-called variable interest entities — legal structures that underpin $2tn of the country’s stocks on US markets. These vehicles have facilitated foreign investment into companies such as Alibaba and Tencent.

The latest development came in mid-August when a Communist party committee declared that it was necessary to “regulate excessively high incomes”, spurring a wave of charitable donations and pledges by leading private sector entrepreneurs to show their alignment with the policy priorities. Stocks in the world’s biggest luxury goods companies, whose growth has been turbocharged by China, also dropped on this apparent aversion to conspicuous consumption.

But as some foreign investors packed their bags, others — many of which have poured years of investment into the country — are standing firm.

Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s biggest hedge fund, told a Bloomberg event on Wednesday that China and Singapore are “a part of the world that one can’t neglect and not only because of the opportunities it provides, but you lose the excitement if you’re not there”.

Those with a more sanguine outlook acknowledge the unpredictable political risk but maintain that regulatory intervention by Chinese authorities is nothing new and its downside is outweighed by the long-term bull story of increasingly wealthy consumers.

Fund managers are not only weighing whether to invest in Chinese assets. They are also considering how to offer their services to consumers there too. Alongside BlackRock, foreign investors including JPMorgan Asset Management and Goldman Sachs Asset Management in the US, and Europe’s Amundi and Schroders are pushing into China with wealth management joint ventures.

BlackRock said in a statement that it wants to provide “our retirement system expertise, products, and services” to China, which “is taking measures to address its growing retirement crisis”. It declined to comment on Soros’ critique.

From an investment perspective, fund managers that are sticking with China say that their strategy is to try to look past the political noise to identify sectors that are aligned with the Communist party’s stated aims, and companies whose valuations are depressed relative to their competitive positions and US or European peers.

“Invesco remains optimistic about the opportunity in China because we think it will be in a growth mode for many years,” said Andrew Lo, head of Asia Pacific at Invesco, a $1.5tn asset manager. It is lifting the amount of money it invests in China securities and increasing the number of analysts it has covering tech companies in the country.

“China is not turning against entrepreneurs and capitalists . . . it remains committed to a sound domestic capital market and wants to have thriving private sector innovation,” he said. Recent regulatory interventions are trying to address monopolistic tech companies and for-profit tutoring companies for the benefit of long-term growth and social welfare, he added.

Lo added that the regulatory clampdown on Chinese tech giants “may mean more small and innovative companies may be able to come to market and provide a more fair and balanced playing field. We expect more listings, more innovation.”

Others are similarly determined to stick with investments because the “common prosperity” policy will herald further growth of the Chinese consumer sector. “Hundreds of millions of people will join the ranks of the spending middle classes in the next few years,” said Mark Martyrossian, chief executive of Aubrey Capital Management, a $1.6bn Edinburgh-based boutique. “If you can find companies with big competitive moats who can tap into that, you can still make huge money.”

Another strategy is, like Ark’s Wood, to try and align with the government’s objectives. “We bought a range of China-facing domestic and international businesses that are plugged in to innovation, the consumer, health and wellness, and technology,” said Jack Dwyer, formerly of Soros Fund Management, who now runs Sydney-based Conduit Capital. “These businesses are valued at material discounts to peers in other jurisdictions.”

Electric vehicles, rare earths and semiconductors also plug in to China’s transition to a green economy and desire to strengthen its domestic supply chain. “When looking at China, I think it might be a question of what could go right, as opposed to thinking that the wheels are falling off,” he said.

Additional reporting by Chris Flood in London