Shortly after beginning to loosen one of the longest and strictest lockdowns in the world, President Alberto Fernández promised in December that 10m Argentines would be vaccinated against Covid-19 by the end of February.

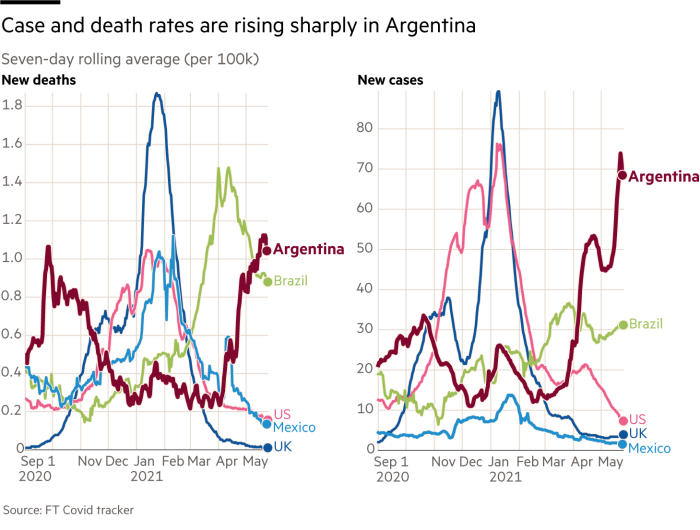

Months later, that promise has still not been fulfilled. Just 9m of Argentina’s 45m inhabitants have received one dose, of whom about 2.5m have received a second. Critics say a faster vaccine rollout could have helped to avoid one of the highest daily death rates in the world, as a second wave sets in.

Now Argentina is in lockdown again to combat a steep rise in cases, which have reached new highs as it heads into winter and more contagious variants from Brazil and the UK spread.

The new lockdown has put pressure on public finances that are stretched to the limit, threatening to extend a recession that has been dragging on for three years.

It has also aggravated an already poisonous political environment, as recriminations fly over the missed vaccine deadline.

On Monday, Fernández sued Patricia Bullrich, a leading opposition politician, for defamation after she insinuated that the government had sought bribes from Pfizer, the US vaccine maker, in return for access to the Argentine market.

“President, you can accuse me as many times as you like, but the vaccines still haven’t arrived and you still haven’t clarified what happened with Pfizer,” Bullrich tweeted.

Bullrich has demanded that Fernández explain why a contract under discussion last year was never signed with Pfizer for more than 13m vaccines that would have started to arrive in December and “saved thousands of lives”. Argentina enjoyed priority status after carrying out important clinical trials for Pfizer last year.

The company said in a statement this week: “Pfizer has not received requests for undue payments . . . In addition, the company does not use intermediaries, private distributors or representatives for the provision of the Covid-19 vaccine.”

Not only has a deal with Pfizer yet to materialise, but a joint venture with Mexico to produce the AstraZeneca vaccine locally ran into delays caused by a shortage of vials and the first lot arrived only this week. Russia has also failed to deliver its Sputnik vaccine on time.

Still, the Russian vaccine accounts for half of the 15m jabs delivered to Argentina so far, with the bulk of the remainder, some 4m, from China’s Sinopharm. That has prompted opposition accusations that the vaccine procurement of Fernandez’s leftist government is motivated by ideological and geopolitical concerns, as Argentina courts Moscow and Beijing.

Although Argentina is doing better than many neighbours in the region’s scramble for vaccines, the problem is the government’s “triumphalism”, which raised expectations too high, according to Adolfo Rubinstein, an epidemiologist who was health minister for the previous government now in opposition.

“They elevated the vaccine programme to epic proportions. Not only did they not deliver, but corruption scandals have eroded society’s confidence and angered many people,” he said. Argentina’s health minister was sacked in February after he was revealed to have personally helped to arrange Covid-19 vaccines for VIPs with government connections.

“Unfortunately the handling of the pandemic has fallen victim to the political divide . . . producing a sterile confrontation which must be de-escalated,” said Rubinstein. “But the government has to move first.”

This toxic atmosphere has complicated the government’s efforts to persuade citizens to stay at home during the current lockdown. This is especially so amid criticisms of unequal treatment; the government’s decision to hold the regional Copa America football tournament in Argentina from next month provoked outrage.

Hugo Pizzi, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Cordoba, says there are only two ways of controlling the pandemic: “You can only get out of such a tragic situation with discipline [in obeying rules aimed at preventing the spread of the virus] and vaccines.” For now, the swift arrival of vaccines in Argentina could be the most promising exit, he thinks, given lax adherence to lockdown rules.

“This [southern hemisphere] winter is going to be tough. I hope that [lockdown] measures are accepted by society, and that the vaccines keep arriving,” said Javier Farina, an infectious diseases specialist advising the government, who hopes that half of Argentines will have received their first jab by August, up from a fifth now.

While the lockdown measures currently in force “need to go on for longer if you only look at sanitary issues, if you consider everything else, the economy carries a lot of weight. The final decision of the authorities will bear that in mind”, he said.

Rubinstein argues that one of the greatest barriers to Argentina’s success in controlling the pandemic is the fact that “Argentines are different, they are less respectful of rules”.

Although initially they adhered to restrictions and Fernandez’s popularity swelled, after the first couple of months of last year’s eight-month lockdown their enthusiasm for Fernández — and following the rules — quickly wore off.

Lockdown fatigue was complicated by confusing signals from the government and Argentina’s large informal economy, which meant that many were forced to seek work outside to pay their bills.

Argentina’s demographics have aggravated the situation further, with a population that is older than countries to the north in Latin America, and so more vulnerable to disease. New, more contagious variants, especially from Brazil and the UK, have fuelled the latest spike in coronavirus cases.

Despite the alarming situation, Pizzi argues that Argentina is not significantly worse off than many of its neighbours in a region that is one of the worst hit in the world. In Paraguay, people were donating chairs so that people could wait in relative comfort in hospital courtyards, he said, while in countries like Ecuador and Peru “corpses piled up in the streets” last year. “It has never been that bad here.”