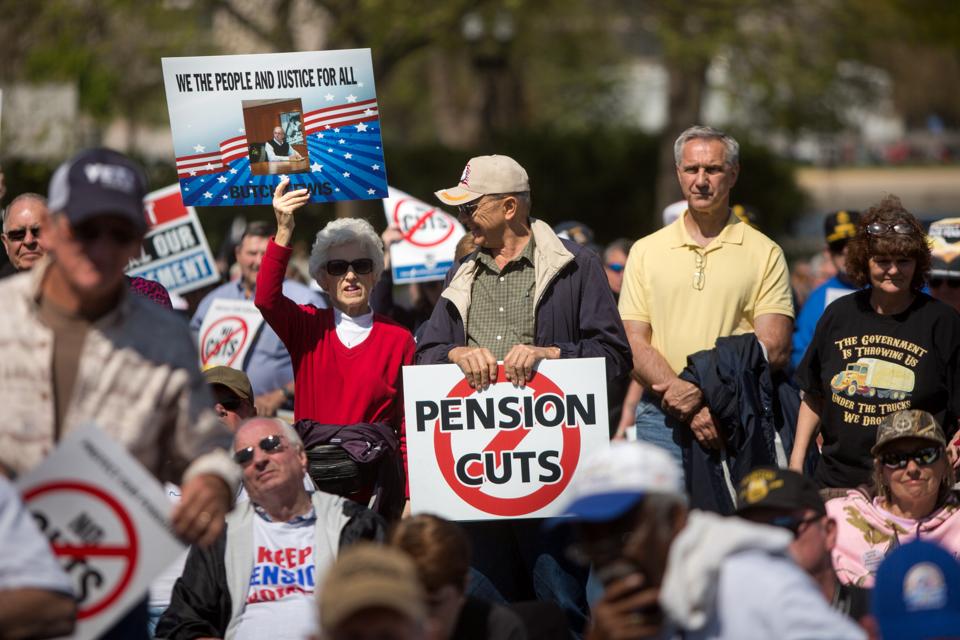

WASHINGTON, D.C. – APRIL 14: Attendees rally on the West Front of the U.S. Capitol building with … [+]

Getty Images

Regular readers will recall that when the Covid relief bill was unveiled, I explained that the bill included a multiemployer pension plan bailout with no preconditions, no reforms, solely the handing-out of cash to qualifying plans, to the tune of $86 billion. To be fair, the requirements of the reconciliation process were responsible for the lack of changes to the funding process, and those who were not a part of the negotiation process cannot know whether one or both political/negotiating parties were being inappropriately intransigent to prevent a resolution to the issue in the normal lawmaking process. However, what’s particularly exasperating to an actuary is the fact that, unlike any other legislation regarding pension funding, the particulars of how this bailout would even work are sketchy and ill-defined: the intention of the bill is to fill in the gaps between available funds and 30 years’ worth of pension benefits, but the law doesn’t specify, for instance, what happens to new employer or employee contributions.

Now the bill has been passed by House and Senate and awaits President Biden’s signature.

What others are saying

Having been harping for years now on the need for a multiemployer pension reform containing true compromise, it was gratifying that major media publications begin to notice this, in the midst of all the talk of the size of and eligibility for the so-called relief checks. Here’s the Washington Post, in an editorial on February 17:

“For years, Republicans and Democrats have tried to negotiate a package to protect workers without soaking taxpayers — most of whom do not even have defined-benefit pensions. Proposals have generally involved some combination of benefit trims, greater employer insurance premiums and federal support. Yet the bill just approved by Ways and Means one-sidedly provides the funds a slug of federal cash, with little structural reform required beyond a somewhat increased employer premium. Its likely net cost: $56 billion.

“To make this pension bailout fit within the $1.9 trillion budget ceiling suggested by Mr. Biden and enshrined in a budget reconciliation resolution, along with $1,400 stimulus ‘checks’ and other spending items, the committee had to offset the cost by ending a much more vital program — extended unemployment benefits — at the end of August rather than September, as Mr. Biden originally advocated. . . .

MORE FOR YOU

“Difficult as the multiemployer plans’ difficulties are, they have a few years of solvency left, time enough to craft a more financially balanced fix through regular order rather than the party-line method of reconciliation. That is the approach that we, along with thoughtful legislators of both parties, have long advocated, and to which Congress should return once it has passed a credible, focused covid relief bill.”

The Wall Street Journal editors wrote, in “The Non-Covid Spending Blowout,” that “The bill includes $86 billion to rescue 185 or so multiemployer pension plans insured by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. Managed jointly by employer sponsors and unions, these plans are chronically underfunded due to lax federal standards and accounting rules. Yet the bailout comes with no real reform.”

The New York Times’ recent article, “Rescue Package Includes $86 Billion Bailout for Failing Pensions,” while taking a “just the facts, ma’am” approach, provides plenty of details about the bailout’s problems:

“Both the House and Senate stimulus measures would give the weakest plans enough money to pay hundreds of thousands of retirees — a number that will grow in the future — their full pensions for the next 30 years. The provision does not require the plans to pay back the bailout, freeze accruals or to end the practices that led to their current distress, which means their troubles could recur. Nor does it explain what will happen when the taxpayer money runs out 30 years from now. . . .

“Using taxpayer dollars to bail out pension plans is almost unheard-of. Previous proposals to rescue the dying multiemployer plans called for the Treasury to make them 30-year loans, not send them no-strings-attached cash. Other efforts have called for the plans to cut some people’s benefits to conserve their dwindling money — such as widow’s pensions, early retirement subsidies and pensions promised by companies that subsequently left their pools. . . .

“While companies that run their pension plans solo must follow strict federal funding rules, multiemployer plans do not have to. Instead, the companies and unions hammer out their own funding rules in collective bargaining. Both sides want to keep the contributions low — the employers to reduce labor costs, and the unions to free up more money for current wages. As a result, many of the plans have gone for years promising benefits without setting aside enough money to pay for them. . . .

“The new legislation does nothing to change that dynamic.”

What happens next?

There is general acknowledgement that multiemployer pensions need reform in their funding methods, not simply a cash infusion. And the bailout’s eligibility is limited to the most-troubled plans, though the number of eligible plans, estimated at 186 by the Congressional Budget Office for the purpose of pricing out the cost of the bailout, could be as high as 336 under certain circumstances, according to the New York Times reporting. Has the bailout created the conditions for this reform? It is possible, I suppose, that now that the dispute about funding has been removed from the picture, discussions about stiffening funding requirements will be more successful, but this seems like only so much wishful thinking. Given that the worst-funded plans have now been made whole, with no benefit cuts, why would multiemployer pension supporters accept what they’ve rejected until now, a more prudent/conservative funding basis?

What’s more, with the precedent having been set, how many more bailouts will we see next?

What about public pensions?

Last week, Andrew Biggs wrote in the Wall Street Journal that this bailout increases the likelihood of a bailout for state and local public pension plans.

“The larger worry is that Congressional Democrats’ willingness to bail out private-sector multiemployer pensions signals they would do the same for state and local employee plans. Public-employee pensions operate under the same loose funding rules as multiemployer pensions, and public plans in Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, Texas and other states are no better funded than the worst multiemployer plans.

“Many public pensions have a history of poor stewardship, increasing benefits in good times and failing to make their pension contributions when the economy turns downward. Will a Democratic Congress turn away unionized public employees when it already has bailed out union-run private sector pensions? At this point, the assumption has to be no.”

On the one hand, generally speaking, public plans are poorly funded, but, unlike the worst multiemployer plans, they are not staring insolvency in the face. Even these worst-of-the-worst plans have contribution schedules which are intended to bring them to full funding, or near-full funding at some point in the future, however far away that may be. And, unlike the multiemployer plans with shrinking numbers of participating employers and lopsided ratios of retired employees to active workers, we generally expect that cities and states’ populations will grow, not shrink.

Yet at the same time, in at least some cases, those contribution schedules place a heavy burden on states, swallowing up huge portions of their operating budgets — upwards of a quarter of Illinois’ budget, for example, or 16% in Chicago (which is not the full expenditure as there are additional sums outside the corporate budget).

This means that there are two means by which the federal government could “bail out” pensions even without those pensions reaching insolvency. In the first case, there might be an “artificial bailout” in which the government intervenes in the accounting standards to enable states to loosen up their contribution schedules and keep their pension plans less funded without an impact on their financial reporting. In the second case, the federal government might permit cities or states which have declared bankruptcy to move their pension liabilities onto the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) just as private-sector plans do, even though public plans have never paid into the system.

What about Social Security?

Will Congress succeed in working out some sort of reform legislation prior to the coming Social Security Trust Fund depletion (which remember, is an arbitrary date in terms of the impact of Social Security on the federal budget but a hard deadline in terms of the need for federal legislation)? I fear the multiemployer bill makes this less likely, by its precedent of a no-compromise full-funding “free money” remedy.

Yes, it is true that Social Security cannot be changed via a reconciliation bill; according to the Byrd Rule (which is not just a custom but law), no changes having to do with “the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program established under Title II of the Social Security Act” may be included in a bill passed through the reconciliation process. But we’ve seen that, under the guise of “covid relief,” provisions have been passed implementing a child benefit and benefits for child care, as well as the $1,400 checks being sent to everyone under the income limits regardless of whether they have financially suffered due to the pandemic.

And Brett Arends, writing at Moneywatch, calls the bailout, “hopeful news for Social Security.” Why?

Because, he writes, given the terms of the multiemployer bailout, and considering that the taxpayers funding the bailout generally don’t themselves have pensions,

“it’s going to be a much bigger scandal if Congress shafts Social Security beneficiaries harder than it does members of these union pensions. It would be ludicrous to hope that shame or embarrassment would constrain most politicians. But right now Social Security beneficiaries could be looking at a 25% benefit cut in just over a decade. . . .

“When the time comes for Congress to address the matter, they’d better give us the same terms as the unions, or we’re going to want to know the reason why.”

Again, strictly speaking, a change to the OASDI provisions of the Social Security Act can’t be done through reconciliation. But we now have precedents for simply handing out cash to whatever group of Americans is deemed worthy, so there would seem to be little standing in the way of handing out an extra benefit, simply not labelled “Social Security” or a part of that structure, to older Americans, rather than reforming the system.

Where to, now?

Unfortunately, likely nowhere. At least in the short term, from all reports, there is no clear path to a next step in the Biden administration’s legislative agenda, no means of seeing whether prior promises of “unity” will materialize. Prior expectations that a big infrastructure bill would be next are now more uncertain, with the State of the Union-like address to Congress pushed as far away as April according to the Washington Post. Likewise, the administration’s immigration proposal, a sweeping change which would have granted mass legalization to essentially everyone in the country without legal authorization, has been dialed back to possible piecemeal changes. One has the feeling that the Democrats in the House, accustomed for many years to passing bills which are symbolic of their positions or perhaps meant as a starting point for negotiations with excessive demands to be conceded later, don’t quite know how to shift to governing in a more reasonable manner, to the degree that they even wish to do so.

As always, you’re invited to comment at JaneTheActuary.com!