Not one of Hong Kong’s top listed companies has achieved gender parity in the boardroom, with the Asian financial hub so far behind global peers that as many white men sit on the boards of its biggest listed groups as women of all backgrounds.

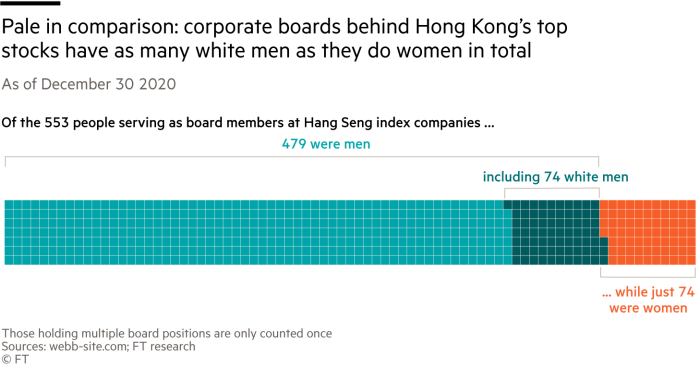

A Financial Times analysis of directorship data tracked by activist investor David Webb shows that at the end of 2020, just 74 women served as board members at the 52 companies in the Hang Seng index. White men, who account for some 0.5 per cent of the Hong Kong population, also made up 74 of the total. More than one-quarter of companies had all-male boards.

Global funds increasingly prioritise board diversity in investment decisions, and some have started voting against the appointment of all-male boards in the city. But as the Hang Seng prepares to welcome more mainland Chinese companies into its ranks, the balance is likely to tip even further in favour of men.

“Hong Kong is missing out and it’s an embarrassment — quotas are the only way to remedy the situation,” said Teresa Ko, China chair at Freshfields and the first woman to become an equity partner at the firm.

Ko opposed quotas when she served as the first female head of the stock exchange’s listings committee from 2009 to 2012. But slow progress has changed her mind. “There are plenty of qualified women, there’s just no impetus for change,” she said.

Quotas are an increasingly popular way to address lagging representation. In December, the tech-focused Nasdaq sought approval to require its more than 3,200 listed companies to have at least one woman and one “minority” board member.

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing — which has a monopoly on stock trading and clearing in the city — has no requirement for companies to have female board members. Instead, applicants with all-male boards must promise improvement within three years of listing, which the exchange says it will “monitor”.

HKEX said it was “committed to driving change [on gender parity], promoting and championing board room diversity and leadership and ensuring that Hong Kong leads from the diversity agenda in the region”.

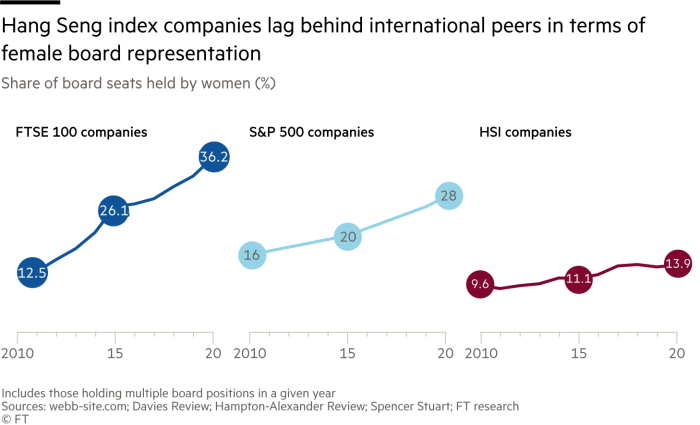

Critics say this approach has yielded glacial gains. Women’s share of Hang Seng index board seats has risen from 9.6 per cent to 13.9 per cent over the past decade, including women who sit on multiple boards.

Over roughly the same period, women’s share of board seats at FTSE 100 companies rose from 12.5 per cent to 36.2 per cent. Among S&P 500 companies, female representation on boards rose from 16 per cent to 28 per cent. Every FTSE 100 and S&P 500 component stock now has at least one female board member.

The gender gap reflected in the city’s top stocks could widen as Hang Seng Indexes pushes forward on reforms that will ultimately double the number of companies in its eponymous benchmark stock index, followed by about $28bn of exchange traded and pension funds.

The move, intended to better reflect the growing bloc of highly valued mainland companies that has dominated listings in recent years, is widely expected to favour Chinese tech groups whose boards are frequently male-dominated.

In Hong Kong, institutional investors have begun voting against the appointment of men to replace outgoing directors at all-male boards. State Street, the Boston-based asset manager, told the FT it had voted against eight such appointments.

“There’s an appetite for more intervention because of how slow the pace of change is,” said Janet Ledger, chief operating officer at Community Business and leader of the group’s initiative to get more women on the boards of listed companies.

Ledger said women often needed to hold comparable board seats already to get offered another opportunity, while low turnover for board members further narrowed opportunities for advancement.

“Unless you’re actually making a concerted effort to go out and look at a broad pool, you’re keeping the club that can be invited to participate smaller,” she said.

The situation outside the Hang Seng is much the same. Across more than 2,500 primary listings in Hong Kong, women occupy just 14.6 per cent of board seats.

Experts in corporate governance say that is partly because many listed companies are owned and run by a family patriarch who is more likely to choose a man to fill out a board primarily intended to serve as a squad of yes-men.

When a family head does elevate a woman to the board, he often chooses a relative, underscoring the need for board diversity and independence that goes beyond a single female director.

“We do think the first female director is an important first step,” said Benjamin Colton, global co-head of asset stewardship at State Street. But he added that meaningful improvement to governance requires more serious changes.

“You shouldn’t need to be the CEO’s wife or daughter,” Colton said. “It’s about expanding the network . . . it’s about accessing talent and refining the nomination process.”

Fiona Nott, chief executive at The Women’s Foundation in Hong Kong, said the city’s lack of parity reflected poorly on its fundamental standards of governance.

“Hong Kong should be embarrassed by the low number of women on boards”, she said. “We’re a global financial centre and in order for us to maintain our standing, [to] have well-governed, high performing companies — diversity is a core element of that.”

Additional reporting by Jane Pong