Everyone knows the poor die sooner than the rich. Some humans can live past 90, but many don’t have access to the health and wealth that lets humans live a normal human life span. In the last 20 years, all longevity gains for Americans have gone to those in the upper half of the income distribution.

Boston University researchers Jacob Bor, Gregory Cohen and Sandro Galea found that income and education gaps in life expectancy widened during the period 1980–2014. Life expectancy for white women without a high school diploma actually declined. “Since 2001, the poorest 5% of Americans experienced close to zero gains in survival. At the same time, middle-income and high-income Americans have gained over 2 years in additional life expectancy.”

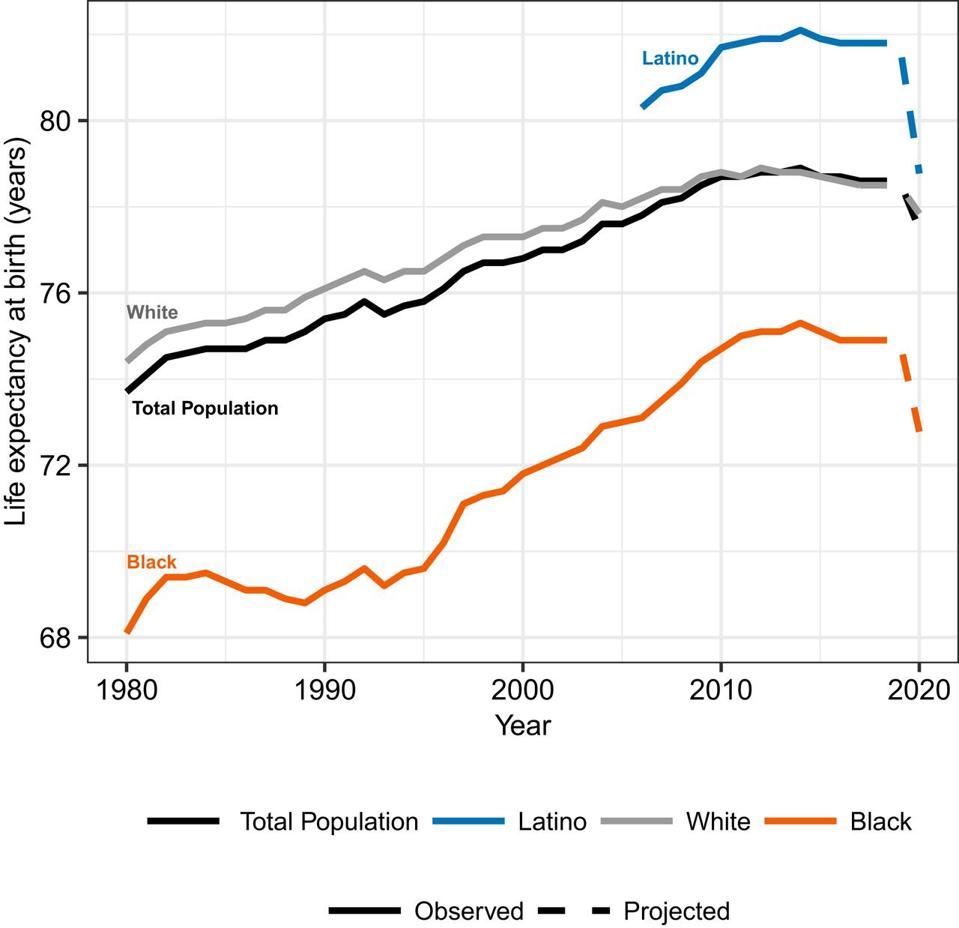

Before the pandemic the class and race gap in longevity was getting worse. In 1950, age-65 life expectancy for Black and white men was equal— each could expect to live about 12.8 more years if they had reached 65. Now there is a 2-year difference (moreover, 81% of white men make it to 65 compared to just 70% of Black men). The only wrinkle in the class-based story was that Latinos had an advantage, even though they were low income. Foreign-born Hispanic men can expect to live 3.2 years longer than their U.S.-born counterparts.

Covid-19 Made Race-Based Longevity Gaps Worse

The Covid-19 pandemic accentuated and accelerated these health differences, with advantaged groups faring relatively well and less advantaged groups suffering more than ever. And COVID-19 reversed the Hispanic advantage. COVID 19-related decrease in life expectancy in the U.S. this year is expected to be more than two and three times higher in Black and Latino populations.

Because of COVID-19 life expectancy in the US is projected to fall by 1.13 year but the reductions for the Black and Latino populations are 3 to 4 times higher than for whites. The new study by University of Southern California (USC) researchers, Theresa Andrasfay and Noreen Goldman, wrote, “Consequently, COVID-19 is expected to reverse over 10 years of progress made in closing the Black−White gap in life expectancy and reduce the previous Latino mortality advantage by over 70%.”

Even worse is the expected increase in morbidity — long-term negative health impacts. People don’t just get COVID-19 and recover or die. There is a big gray area in-between where many are affected long term by the disease. And, women of color are the most disabled members of the American population.

Changes in life expectancy at birth by race.

Theresa Andrasfay and Noreen Goldman

The End of the Hispanic Paradox

As the University of Southern California Study showed COVID-19 seems to be on track of eliminating the paradox that Hispanic-Americans had higher expected longevity — after age 65 – than whites. White men had 17.7 years of expected life after age 65, Hispanic American men had 18.8 years. White women had 20.3 years of expected life after age 65, while Hispanic-American women had 22 years.

Why a paradox? Hispanic-Americans aren’t rich, but they live longer. A 2013 study showed, the Hispanic population had a 17.5% lower risk of mortality, averaged over the life course, compared to non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites. But, the superiority depends on country of birth. On average, white men, live an additional 2.3 years free of disabilities compared to U.S.-born Hispanics.

Longevity And Disability Gaps Expected to Grow

But the USC study is hard hitting and a call to action. To close gaps, I want to shout out to California that doubled the allocation of COVID-19 vaccines for places with the lowest Healthy Places Index (HPI) – an index which reflects 25 community characteristics related to the economy, education, healthcare access, housing, neighborhoods, clean environment, transportation, and social environment between between March 2-8.

The Kaiser Family Foundation is tracking what states are doing to ensure equity. And The Biden administration’s national COVID-19 response strategy identifies equity as a key priority in vaccine distribution.

The USC study notes, many factors contribute to race and class longevity differences. Non Whites hold lower-paying jobs with little autonomy, more risk of unemployment and loss of health insurance. Undocumented Latinos are often ineligible for government unemployment benefits or consistent health care. Non-Whites have generally poorer quality of care inside and outside of hospitals. Black adults generally have higher rates of hypertension, obesity, diabetes, cancer, and heart disease.

Approaches to public health will have to incorporate more pro-equity plans for health care, not just the vaccine distribution, than ramping up more equal distributions of vaccines and testing. Equal access to health care is a good first step to close racial and class longevity and morbidity gaps, without it the racial and socio-economic gaps in morbidity and longevity will get worse.