Juan Guaidó rose to his feet in the gallery of Washington’s Capitol building and waved stiffly to acknowledge cheers and applause from members of Congress as President Donald Trump’s words rang in their ears.

“Here this evening is a very brave man who carries with him the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of all Venezuelans . . . the true and legitimate president of Venezuela, Juan Guaidó,” said Mr Trump. Dismissing President Nicolás Maduro as an illegitimate dictator, the US leader promised that “Maduro’s grip on tyranny will be smashed and broken”.

But less than a year after his guest appearance at the State of the Union address capped a triumphant overseas tour, it is Mr Guaidó who appears broken while Mr Maduro’s hold on power seems stronger than ever.

The failure of US policy on Venezuela comes as the political, economic and humanitarian crisis in the South American oil exporter deepens, presenting the incoming Biden administration with one of its biggest foreign policy challenges.

Five million people have fled the Maduro regime, creating the worst refugee crisis in the Americas and threatening the stability of neighbouring countries. The once-wealthy economy lies in ruins. Criminal gangs now control increasing portions of Venezuelan territory. Diplomats are talking of the risk of a large failed state appearing on the edge of the Caribbean.

On January 5, Mr Guaidó will lose his presidency of the National Assembly, and with it the legal basis for his claim to be Venezuela’s interim leader as a new crop of pro-Maduro legislators are sworn in. They won a landslide victory in elections boycotted by the opposition and condemned abroad as neither free nor fair, but Mr Maduro has nonetheless succeeded in bringing to heel Venezuela’s last democratically-controlled institution.

This poses a painful dilemma for the US-led coalition of nearly 60 nations in the Americas and Europe who recognised Mr Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate interim ruler in early 2019: do they continue with an increasingly untenable status quo or drop Mr Guaidó and risk legitimising Mr Maduro’s control?

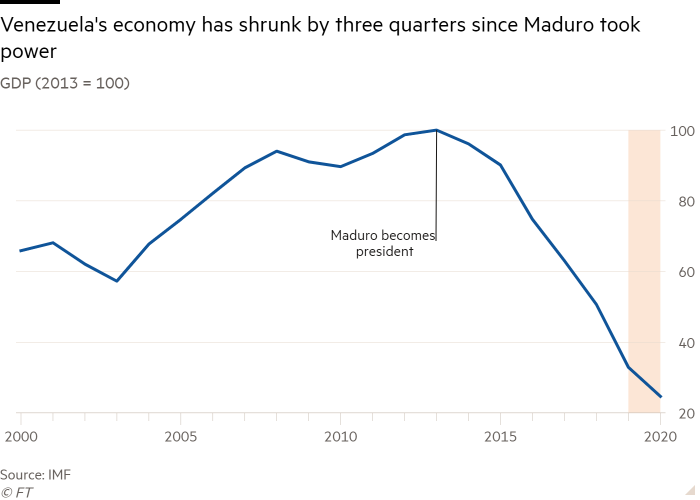

Such a situation was never supposed to arise. Dismissed by many as a clumsy incompetent when he succeeded the late Hugo Chávez in 2013, Mr Maduro, a former bus driver, had neither his predecessor’s charisma nor his popular support and seemed unlikely to last.

Washington launched a relentless onslaught to try to force regime change. Mr Trump imposed crippling sanctions, hinted several times at military intervention and assembled the formidable diplomatic coalition behind Mr Guaidó in the hope of toppling Chavez’s heir.

In April 2019, Mr Guaidó even launched an uprising from the streets of Caracas, calling on army units to desert Mr Maduro and join a popular revolution. US officials said at the time that senior regime officials had privately indicated they were willing to switch sides and back Mr Guaidó. But the revolt fizzled as soon as it began.

As the pressure on him grew, Mr Maduro turned to his backers in Moscow, Beijing, Tehran and Havana. With the flow of petrodollars hit by US sanctions and a collapse in crude production, his regime diversified into drug trafficking, illegal gold mining and timber trading to provide vital foreign exchange, US officials say.

In a divided nation, ordinary Venezuelans must queue for food and fuel and endure regular interruptions of water and electricity services. But large SUVs still wend their way through the Caracas streets, taking well-connected insiders to hard currency stores where they can load up on imported luxuries or to visit fancy clubs and party the night away.

“Look around you! Some people are still living very well indeed, while we’re scrambling to find food, petrol, water and gas,” says Marely Reyes, a resident in the poor neighbourhood of La Pastora. “And this in a supposedly socialist country.”

‘Reality is reality’

An increasingly repressive government has kept a battered and exhausted population in check. After Chávez, Mr Maduro is now the longest-serving leader in Venezuela in nearly a century. His public performances are less frequent — with his approval ratings at around 14 per cent, he knows he is hated by a large part of the population and cannot easily venture out on to the streets — and yet they are more assured.

At a news conference last month to celebrate his election victory, he joked with reporters and looked like a man in control of his destiny.

Asked what would happen next in Venezuela, Mr Maduro replied that reality would prevail “and fantasy is going to disappear from the political life of the country” — a clear reference to Mr Guaidó’s shadow government. “It doesn’t matter if the US or Europe or the Martians support that fantasy. Reality is reality and it’s very powerful.”

Mr Guaidó, by contrast, cut a forlorn figure last month as he campaigned in Caracas, urging people to boycott the National Assembly election and participate instead in an opposition-led online referendum on Mr Maduro’s rule.

When he arrived in Cumbres de Curumo, a well-to-do suburb in the south of the city, an enthusiastic crowd was there to greet him. But it was no more than 200 people — a fraction of the huge numbers who took to the streets to support him in early 2019.

Mr Guaidó’s message was the same — “we cannot allow a dictatorship to become the norm in 21st century Venezuela” — but it is a warning that has run up against harsh reality.

His coalition was tarnished in May by links to a botched incursion by US mercenaries and is divided over unpopular decisions to back US sanctions and to boycott the parliamentary election.

Luis Vicente León, an independent pollster in Venezuela, says Mr Guaidó’s poll ratings had plunged from a peak of 61 per cent in February 2019, shortly after he declared himself president, to 25 per cent in October this year, not far off Mr Maduro’s 14 per cent. Both men are far outnumbered by what are called “ni-nis” in Spanish — the 56 per cent who want neither of them.

“Most people reject Maduro, they want a change of government but most people also reject abstention and they reject sanctions,” Mr León says. “I’ve never foreseen a worse moment for the opposition than January to March 2021.”

How to treat Caracas

While Mr Guaidó struggles to retain support at home and abroad, the incoming Biden administration must consider whether to stick with the failed Trump-era “maximum pressure” policies on Venezuela or to try a new approach. A major constraint will be US domestic politics.

In one of the bigger upsets of the US election, Mr Trump won the crucial swing state of Florida by more than 370,000 votes, a margin more than twice as large as in 2016. Two Democrats in south Florida lost their House of Representatives seats to Cuban-American Republicans.

One of the keys to the Republican victories in the Sunshine State, analysts say, was Mr Trump’s relentless attacks on his Democratic rival Joe Biden as “soft” on Mr Maduro’s government and that of his communist allies in Cuba — regimes which many of Miami’s Latino exiles had fled.

“Joe Biden — the candidate of ‘chavismo’” read the banner on a YouTube Trump campaign ad viewed more than 100,000 times in Florida in October, showing images of Mr Biden greeting Mr Maduro at a 2015 presidential inauguration in Brazil.

The irony is that, despite four years of fierce rhetoric, crippling sanctions and the unprecedented diplomatic push for Mr Guaidó, the Trump administration failed to achieve political change in Venezuela.

“For Trump, Venezuela was not foreign policy, it was a domestic matter,” says a senior EU official. “His policy worked for him — he won Florida because of the Hispanics, mainly the Cubans and the Venezuelans. He realised that he could win votes by imposing tougher and tougher sanctions.”

The electoral success in Florida of Trump’s hardline policies has created an awkward dilemma for the incoming Biden administration.

“Venezuela has been caught up in a war between Cubans,” says the EU official. “It’s become a fight between Cubans on the island [who back Maduro] and Cuban exiles in Miami . . . the question is whether Joe Biden will be capable of going back to treating Venezuela as a foreign policy issue with the same objective we have, namely of preventing a big black hole of a failed state from opening up on the Caribbean.”

Mr Biden’s Latin American aides are not commenting publicly on policy ahead of the inauguration this month but the new US president is not expected to make big changes to Venezuela policy early on, diplomats say. The immediate focus is likely to be on easing the humanitarian crisis and exploring possible paths for talks, while continuing to recognise Mr Guaidó. The UK is likely to follow the Americans’ lead.

The EU is less certain about continuing to formally recognise the Venezuelan opposition leader. Several member states are unhappy about treating Mr Guaidó as the country’s legitimate president when the facts on the ground clearly point in the opposite direction.

European diplomats have prepared a paper for EU foreign ministers offering three options: continuing with the status quo, dropping recognition of Mr Guaidó completely or a middle way: recognising him as the leader of a united opposition but not as the interim president. The latter is seen as the most likely to succeed.

Latin American nations have mostly backed Mr Guaidó so far but are growing increasingly nervous about the possible precedents it might set. “Peru, for example, went through three presidents in a week last month,” says one envoy from the region. “What would happen if other countries decided to recognise one of Peru’s previous presidents?”

Making dialogue work

Mr Maduro’s international backers, meanwhile, are standing firm. Russia sent observers to last month’s election, Iran has dispatched technicians to help rebuild Venezuela’s shattered oil refineries, Cuban agents provide vital intelligence and personal protection for Mr Maduro and Chinese firms continue to buy Venezuela’s crude oil.

“This shows you how misguided US policy has been,” says a former senior Obama-era administration official. “If you create a situation in Latin America where Russia, China and Cuba become key players in reaching a political solution, then you’ve really screwed up.”

Trump administration officials reject the idea that their Venezuela policies have failed and insist that Mr Maduro’s situation is worse than it appears. The US has indicted Mr Maduro and his key allies for drug trafficking and other crimes, meaning they risk arrest if they travel internationally. There are divisions within the Chavista elite over whether to negotiate. The dire economic situation is not sustainable long-term. The International Criminal Court said this month there was a “reasonable basis” to believe Venezuela had committed crimes against humanity with its extrajudicial killings and torture.

Elliott Abrams, US special representative for Venezuela during the Trump administration, says the regime is not held together by loyalty to Mr Maduro or even by the lure of money but “by collective criminal liability”.

“This is what differentiates them from many military regimes in South America that negotiated a democratic transition,” he says. “They were not gangs of criminals. They were military groups who had conducted a coup. That’s not the case here . . . it’s a criminal regime engaged in activities like drug trafficking.”

Trump administration officials, who until late last year routinely referred to “President Guaidó” and the “former Maduro regime”, now privately recognise that the Venezuela opposition needs to change tack, give up its pretensions of being a shadow government and return to campaigning in the streets.

Optimistic predictions that the regime would buckle under the pressure of sanctions have given way to a realisation that there is no alternative to talking to Mr Maduro. But multiple rounds of talks brokered by international mediators over the past few years have failed to produce results.

María Corina Machado, a hardline opponent of Mr Maduro who has also been critical of Mr Guaidó, says there have been 13 different initiatives aimed at dialogue and all have failed. “These people are not going to leave power peacefully,” she says.

Will the Biden administration, already facing huge challenges at home from the coronavirus pandemic and overseas as it tries to rebuild alliances strained by the Trump years, want to expend precious energy on a long, complex and risky diplomatic effort to resolve Venezuela?

“I think the question is whether the regime is willing to open any political space [to negotiate],” says Mr Abrams. “I’m sure a Biden administration will find out the answer to that.”

Pressed on his own view, Mr Abrams concludes: “Every indication is that the answer is ‘no’.”