When Donald Trump was furiously contesting his election defeat in the courts, the then US president still found time for at least one foreign visitor to the Oval Office.

Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s minister for maritime affairs and investment, was given the red carpet treatment by the Trump family late last year, extracting what he claimed was a promise of $2bn in funding for Indonesia’s first sovereign wealth fund.

The apparent financial backing might be moot, following Mr Trump’s departure from office last week. But for Indonesians, the episode underlined the remarkable networking ability of one of south-east Asia’s leading political dealmakers, who has become Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s “minister of everything”.

From raising funds for the sovereign wealth fund to coordinating one of the world’s biggest vaccination programmes, the mustachioed former general has become the government’s Mr Fixit.

“President Jokowi remains the main political figure in terms of palace politics and cabinet day-to-day activities,” said Philips Vermonte, executive director at CSIS Indonesia, a think-tank. “But Pak [Mr] Luhut is a fixer, a doer. Whatever task is given to him, he seems to be able to deliver.”

A Christian born on the island of Sumatra, he saw combat as a young officer during the 1975 invasion of the former Portuguese colony of East Timor by the late Indonesian dictator Suharto. Now 73, he once described how some of his men had soiled their trousers as they prepared to parachute into the capital, Dili, kicking off a war that cost an estimated 100,000 lives.

Mr Pandjaitan rose to general and became a minister after Indonesia started its transition to democracy in 1998, before leaving politics to set up his own business. His interests include timber, property, palm oil, coal mining and energy.

In 2008, he met Mr Widodo, then a city mayor, and helped finance his victorious presidential election campaign in 2014. Two years later, while he was briefly minister of mines and energy, he sold a controlling stake in his coal unit, Toba Bara, for an undisclosed amount to a Singapore-based company whose ultimate buyers remain unidentified.

The lack of details on the sale “has left unanswered questions which are an important matter of public interest”, said Global Witness, a campaign group. The ministry of maritime affairs and investment said the buyers are “a non-related party to Mr Pandjaitan and/or Toba”.

Mr Widodo, who came to power promising to tackle Indonesia’s endemic corruption, has continued to load Mr Pandjaitan with new responsibilities throughout. Not only is the ex-general involved in the vaccine drive and the sovereign wealth fund, he is also courting investors for a planned $31bn new capital city.

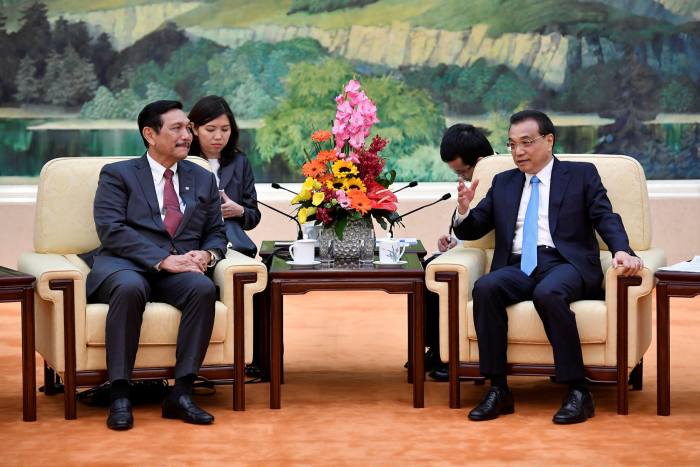

On the international stage, Mr Pandjaitan was pictured in October tapping elbows with Wang Yi, China’s foreign affairs minister, as Jakarta sought Chinese vaccines. Only a year earlier, he had led Indonesia’s response to the incursion of Chinese fishing boats in waters claimed by Jakarta near the South China Sea.

Fluent in English after studying in the US, the former general’s connection with the Trump administration is through Jared Kushner, Mr Trump’s son-in-law, whom he met at the White House at least two years ago. “We maintained this [relationship] so we can talk over the phone or maybe [on] WhatsApp,” Mr Pandjaitan told the Financial Times last year.

The dialogue between the pair became “the main bilateral relationship between DC and Jakarta”, said Aaron Connelly, a research fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank.

Mr Trump’s family also has business interests in Indonesia. Donald Trump Jr, the former president’s son and executive vice-president of the Trump Organization, last year launched two Trump-branded resorts in the south-east Asian country.

It remains to be seen, however, whether Mr Pandjaitan will be able to replicate these close ties with the White House under Joe Biden, the US’s new president.

And for all Mr Pandjaitan’s rising status, analysts say he probably will never be president of Indonesia. The Muslim majority country would be unlikely to vote for a Christian leader.

But as long as Mr Widodo is in power, he is expected to be the president’s de facto prime minister, with cameo roles in defence, foreign affairs and international investment.

“I think for him it’s just a power thing,” said an Indonesian politician who is familiar with Mr Pandjaitan. “Right now he can have a lot of power without really playing the politics of it . . . That’s where he wants to be.”