Robinhood’s quest to disrupt Wall Street with its sleek app and promise to “democratise” trading has itself been disrupted by a duo of US regulatory actions that highlight the tougher scrutiny the Silicon Valley broker faces.

The broker agreed a $65m settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission on Thursday over allegedly failing to deliver value for clients, just days after accusations by the Massachusetts Securities Division that it has “gamified” investing.

The moves show the pressure the $11.7bn upstart is under as it looks to compete with established rivals like Charles Schwab and ETrade.

While Robinhood has drawn millions of Americans into the financial markets with its no-commission approach, analysts say the company must now manage the delicate transition from scrappy tech start-up to a significant player in the highly-regulated financial industry. The challenges present a new roadblock to Robinhood, and they cut to the heart of its business just as its leaders push ahead with an initial public offering.

“What you have is a populist who is trying to bend all the rules and running into regulatory scrutiny,” said John Coffee, a professor at Columbia Law School who specialises in financial regulation.

Robinhood has rushed in recent months to shift from disruptive outsider to a part of the establishment with a series of hires from competitors. The recruitment drive has bulked out its compliance teams, with the majority of employees in those departments having joined over the past three months, Robinhood said.

Robinhood hired two chief compliance officers in September, Norm Ashkenas, formerly the head of compliance at Fidelity, and Kelly Zigaitis, from Wells Fargo where she worked as head of oversight and controls. Former Goldman Sachs lawyer Janet Broeckel has taken over regulatory enforcement and litigation at the platform.

Professor Coffee warned, however, that despite the changes made in recent months, “beefing up compliance won’t necessarily work if you’re still pushing risky investment strategies like day trading”.

The Massachusetts regulator struck at this issue when it censured Robinhood this week over its push to find new customers, many of whom were inexperienced, and coax them to trade. The watchdog found more than two-thirds of the residents in the state who had been approved to trade options had little or no investment experience.

The group’s zero-commission model relies on high trading volumes, and it encourages users to the platforms with frequent email updates, mobile phone alerts and emoji-laden messages. Confetti blasts, which pop up when customers complete trades, add to the sense that it is a game.

Users receive free shares in popular companies for bringing their friends to the platform. Robinhood has at times been overwhelmed by its user volume, and experienced roughly 70 outages or disruptions since the start of the year, according to the Massachusetts regulator.

The regulator said the company used “gamification strategies to manipulate customers” to trade over and over again.

“It has become like Candy Crush in the way they have engaged with user attention-grabbing techniques first developed in Silicon Valley,” added Paul Rowady, a director at Alphacution, which does research on trading firms.

Robinhood has disputed the Massachusetts charges and said it would defend itself.

A group of academics highlighted similar concerns in a paper published in October that said Robinhood’s simplified user experience, which features shortlists of popular shares each day, drives novice investors into “extreme herding episodes”. Investors all buy the same shares, driving up the price and hurting their returns, the researchers found.

“A lot of the good things Robinhood did started from good intentions,” said Xing Huang, co-author of the study and a finance professor at Olin Business School at Washington university. “They made the stock market simpler and financially accessible. But we need to understand that there is a dark side to these measures.”

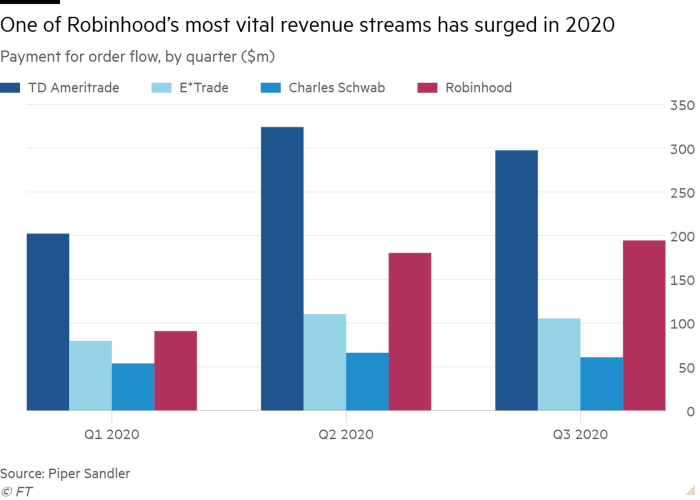

The SEC complaint centred on one of Robinhood’s most vital revenue streams: the money it receives from market makers who process its clients’ trades, a practice known as payment for order flow.

Robinhood had negotiated rates with these high-speed trading firms that were “significantly” higher than the deals other online brokerages had cut, leading to inferior pricing or “execution” on its customers’ orders, according to the SEC complaint.

The group earned these higher fees at the expense of its customers who would have saved $34m combined if they had gone to a competitor between 2016 and 2019, the SEC said. The company neither admitted nor denied the charges.

“The settlement relates to historical practices that do not reflect Robinhood today,” said Dan Gallagher, Robinhood’s chief legal officer. “We recognise the responsibility that comes with having helped millions of investors make their first investments, and we’re committed to continuing to evolve Robinhood as we grow to meet our customers’ needs.”

The company could yet face litigation from customers that the SEC and Massachusetts alleged were harmed by its practices, said Charles Whitehead, a professor at Cornell Law School.

Paul Helms, a partner at law firm McDermott Will and Emery and a former attorney in the SEC’s enforcement division, said the regulatory actions could push the company to rethink its business model and look to new revenue streams.

“The hard question that the settlement raises is: can their model satisfy their best execution obligations?” Mr Helms asked.