Coronavirus did much to shape the book world in 2020 — and will continue to do so in the new year, whether in the form of titles postponed by the pandemic or as the subject of new ones. January brings the first of a number of dispatches from the frontline of the crisis — Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke (Little Brown) and Intensive Care by Gavin Francis (Profile), which detail the heartbreaking realities of a healthcare system under extreme pressure.

For others, Covid-19 is a departure point for bigger investigations of flawed politics and economics, and the spur to outline a better future. In Doom (Allen Lane, May), historian Niall Ferguson asks why humanity is so bad at preparing for disasters. For economist Mariana Mazzucato, the crisis has provided an opportunity to remake capitalism, a case she argues in Mission Economy (Allen Lane, January). Others spotting opportunity in a crisis include former UK prime minister Gordon Brown with Seven Ways to Change the World (Simon & Schuster, June). On a more ambivalent note, economist and habitual gloomster James Rickards tallies up the winners and losers of a post-pandemic world in The New Great Depression (Portfolio, January).

As 2020 came to a close, coronavirus seemingly collided with that other dominating issue in Britain — Brexit — as the recent tailback of trucks at Dover appeared to offer a taste of chaos to come. How we got here and where we might now go are the subject of numerous new books. In January, in This Sovereign Isle (Allen Lane), Robert Tombs, professor of history at Cambridge and prominent Brexiter, argues that Britain has always been different from the rest of Europe; meanwhile FT columnist Philip Stephens charts Britain’s post-imperial geopolitical path from Suez to Brexit in Britain Alone (Faber).

Veteran diplomat Peter Ricketts considers the options facing post-EU Britain in a fast-changing world in Hard Choices (Atlantic, May); in How Britain Ends (Head of Zeus, February), journalist Gavin Esler asks whether the nationalist sentiments that informed Brexit could result in the break-up of the United Kingdom. An earlier fracturing of the UK is addressed in Charles Townshend’s The Partition (Allen Lane, April) which looks at the events leading up to Ireland’s independence and division 100 years ago. With his account of the crushing defeat of Jacobite forces, Paul O’Keeffe’s Culloden (Bodley Head, January) promises poignant reading in a year when, in the wake of Brexit and forthcoming Scottish Parliament elections, the issue of Scottish independence is set to loom large on the UK political agenda.

The defining importance of constitutions is the subject of The Gun, the Ship and the Pen (Profile, March) by Linda Colley, the acclaimed historian of British nationhood and imperialism. The legacy of empire, often cited as one of the driving forces behind Brexit, is the subject of Sathnam Sanghera’s new book Empireland (Viking, January), which looks at how imperialism has shaped modern Britain. The realities of Muslim Britain and the associated tensions, ignorance and hostilities are the subject of Among the Mosques (Bloomsbury, June) by former Islamist activist Ed Husain.

In The Aristocracy of Talent (Allen Lane, June), Adrian Wooldridge takes aim at meritocracy, exploring how it shaped the modern world and has now come to blight it. The sense of a nation not at ease with itself is amplified in Alwyn Turner’s All In It Together (Profile, June), a wide-ranging portrayal of the UK today; while Selina Todd turns a critical eye to the “myth” of social mobility in Snakes and Ladders (Chatto & Windus, February).

February also sees the launch of Black Britain (Hamish Hamilton), a series of “lost or hard-to-find” books by black authors. Curated by Booker prize winner Bernardine Evaristo, the series — which will kick off with six titles, ranging from thrillers to historical fiction — is part of a broader initiative to correct a historic bias within British publishing.

Museums are another national institution facing questions about their purpose — and the provenance of their collections. Expect the debate to continue in 2021 with the likes of Barnaby Phillip’s Loot (Oneworld, March), an account of the story of the Benin bronzes of the British Museum. Meanwhile in The Art Museum in Modern Times (Thames & Hudson, March) Charles Saumarez Smith, former director of London’s National Gallery, looks at the evolution of the modern museum and asks whether it has a future. Moving to the contents of museums, Jennifer Higgie brings an overdue focus to self-portraits by women artists in The Mirror and the Palette (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, March).

The history of London would have been very different without Mary Davies, heiress to a slice of land that would become some of the most valuable real estate in the world and the cornerstone of the fortunes of the dukes of Westminster. Yet her story — one of wealth, madness and unhappiness — has been largely forgotten, something Leo Hollis hopes to correct in Inheritance (Oneworld, May). April brings another historical insight with Sean McMeekin’s Stalin’s War (Allen Lane), which revisits the story of the second world war from a less-familiar perspective, that of the Soviets.

Back in the present day, the challenge of climate change unsurprisingly also figures prominently. Ones to note include February titles from Bill Gates with his solution-based offering How to Avoid a Climate Disaster (Allen Lane) and Under a White Sky (Bodley Head) by New Yorker writer Elizabeth Kolbert. Among novelists drawn to the subject is Richard Flanagan, whose The Living Sea of Waking Dreams (Chatto & Windus, January) explores the climate emergency through a familial crisis.

Another big topic on the global agenda for 2021 will be US-China relations and how they are reset by President Joe Biden. In The World Turned Upside Down (Yale, January), Clyde Prestowitz, leader of the first US trade mission to Beijing, calls for a more sophisticated strategy towards China rather than the narrow trade scraps of recent years. Confusingly — or perhaps tellingly? — the title is one shared with Yang Jisheng’s latest book, though the subject is very different: a history of the cultural revolution. In his The World Turned Upside Down (Farrar Straus and Giroux, January) the acclaimed journalist offers a highly detailed account of one of the most terrifying moments in recent Chinese history. For Roger Garside, today’s rulers in Beijing are less secure than they may appear. In China Coup (University of California Press, May), he ponders the end of one-party rule.

The new year brings a number of notable biographies. In Francis Bacon (William Collins, January), Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan claim the first “fully comprehensive” — it’s certainly a hefty tome — biography of the celebrated artist. Similarly, Philip Roth (Jonathan Cape, April) by Blake Bailey is the first major portrayal of the novelist, who granted the author full access and independence before his death in 2018. The 200th anniversary of the death of Keats in marked by Lucasta Miller in Keats (Jonathan Cape, February), a “brief life in nine poems and one epitaph”.

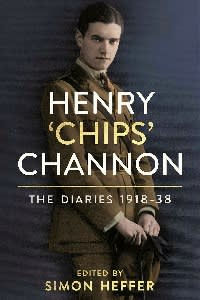

A more recent fount of ideas, Edward Said, is the subject of Places of Mind, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, March) a biography by Tim Brennan, who explores the influences on his friend and former teacher. Also much-anticipated are the first volume of The Diaries of Chips Channon (Hutchinson, March), edited by Simon Heffer. One of the many titles postponed from 2020 due to Covid-19, the diaries of the American-born British MP and socialite promise to be a treat. Channon’s career may have been unremarkable; his social life was anything but. John Sutherland’s Monica Jones, Philip Larkin and Me (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), a biography of the poet’s lover and muse, has generated keen interest ahead of its publication in April.

A more sinister chord is struck by Michela Wrong’s Do Not Disturb (4th Estate, April), which examines the controversial life of Paul Kagame and the legacy of the Rwandan genocide. On a more personal note, May brings the final instalment of Deborah Levy’s “living autobiography” Real Estate (Hamish Hamilton), in which the writer turns her attention to the subject of home. And following the success of Another Planet, her 2019 memoir of suburban ennui, Tracey Thorn turns to her later home in My Rock ‘n’ Roll Friend (Canongate, April), where she explores the women and female friendship in music.

Turning inwards, Veronica O’Keane looks at memories — how we make them and how they shape us — in The Rag and Bone Shop (Allen Lane, February). Our mental health is the subject of several new books on depression — starting in January with two personal accounts, Mending the Mind by Oliver Kamm (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) and The Limits of My Language by the Dutch writer Eva Meijer (Pushkin Press).

In 2020 many of us were reminded of the joys and wonders of the natural world — if only because we were denied them for much of the year. For anyone who came away from Colum McCann’s 2020 Booker-longlisted novel Apeirogon astonished at the tales of migratory birds, Scott Weidensaul’s A World on a Wing (Picador, March) offers a deeper dive. Helen Gordon brings things down to earth in Notes from Deep Time (Profile, February) where she invites us to read the story of our planet in its landscape.

Best Books of the Year 2020

All this week, FT writers and critics share their favourites. Some highlights are:

Monday: Business by Andrew Hill

Tuesday: Economics by Martin Wolf

Wednesday: Politics by Gideon Rachman

Thursday: History by Tony Barber

Friday: Critics choice

Saturday: Crime by Barry Forshaw

In the coming year, a number of books map out how to change tack. In Reset (House of Anansi, January) Ronald Deibert sketches out a plan to reclaim the internet for civil society, while Tara Dawson McGuinness and Hana Schank make the case for public internet technology in Power to the Public (Princeton, April). As anyone who has watched that revelatory YouTube video of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny and a secret service agent, Bellingcat is a highly effective investigative journalism website. The group’s founder Eliot Higgins tells the bigger story in We Are Bellingcat (Bloomsbury, February).

Technology also features prominently among the business books of 2021. The mega-tech investment phenomenon that is SoftBank is the subject of Aiming High (Hodder & Stoughton, June), Atsuo Inoue’s biography of the group’s founder Masayoshi Son. The Founders by Jimmy Soni (Atlantic, May) tells the story of Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and the group of disrupters who “made” the modern internet. In Fulfilment (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, March), Alec MacGillis brings the latest investigation into Amazon and its impact on small town, Main Street America. Another corporate controversy is explored in Patrick Radden Keefe’s “secret history” of the Sackler family, Empire of Pain (Picador, May). Other notable business reads include The World for Sale (Random House Business, February) in which Javier Blas and Jack Farchy probe the hard-knuckle and secretive world of commodity trading.

Some of the breathtaking and far-reaching developments coming out of the laboratory are detailed in The Code Breaker (Simon & Schuster, March), Walter Isaacson’s account of Jennifer Doudna and her pioneering work on gene editing, for which she was awarded a Nobel Prize. The implications of scientific innovation for humanity have also captured the imagination of some of literature’s biggest names, including Kazuo Ishiguro, whose novel Klara and the Sun (Faber, March) imagines the everyday realities of artificial intelligence. AI featured heavily in Jeanette Winterson’s 2019 Frankissstein, a reimagining of Mary Shelley’s gothic classic; in 2021 she returns to the subject in a series of essays 12 Bytes (Jonathan Cape, June). Meanwhile, Edward St Aubyn, well known for his dissolute and damaged Patrick Melrose novels, explores new ground with Double Blind (Harvill Secker, March), which will touch on the fields of “ecology, genetics, neuroscience and psychoanalysis”.

With fiction schedules still playing catch-up after the disruption of last year, 2021 gets off to a busy start. Kate Mosse fans will be eagerly awaiting The City of Tears (Mantle), the next book in The Burning Chambers series, which is published in January. The following month, Francis Spufford, best known for his award-winning 2016 novel Golden Hill, returns with Light Perpetual (Faber, February) and Viet Thanh Nguyen publishes The Committed (Corsair). Stephen King’s new novel Later (Hard Case Crime, March) looks set to be one of the highlights of the spring season for many readers.

This early part of the year is a fertile time for several millennial writers who have already established themselves as names to watch. Olivia Sudjic’s new novel Asylum Road (Bloomsbury, January) follows her success with 2017’s Sympathy, while Fiona Mozley, whose debut Elmet was shortlisted for the 2017 Man Booker, returns with Hot Stew (John Murray, March). There is also considerable excitement ahead of Yaa Gyasi’s new book Transcendent Kingdom (Viking, March).

Meanwhile, Jeet Thayil’s retelling of the New Testament from the female point of view — Names of the Women (Jonathan Cape, March) — is one of several high profile feminist novels due to be published in the early summer; Lisa Taddeo, whose debut, an account of female desire titled Three Women, was a bestseller in 2019, is back with a novel: Animal (Bloomsbury, June); and Rachel Cusk offers a “study of female fate and male privilege” with her new novel Second Place (Faber, May).

Wole Soyinka’s Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (Bloomsbury) — a story set in contemporary Nigeria, and the Nobel laureate’s first novel in 47 years — will be one of the clear highlights of late summer.

Poetry may not have suffered the same raft of delays as fiction, but 2021 looks like a bumper year. In January, US poet Rowan Ricardo Phillips releases his first UK book, Living Weapon (Faber), while Picador opens the year with Annie Freud’s Hiddensee. Granta’s poetry series continues with Comic Timing, the debut from Forward prize winner Holly Pester (February); another promising debut is Bird of Winter by Alice Hiller, who writes about difficult subjects to stunning effect (Pavilion, April). Fans of Michael Symmons Roberts will have Ransom in March (Jonathan Cape), while Kayo Chingonyi’s A Blood Condition is based on themes of inheritance (Chatto & Windus, April). Rachael Boast’s formal prowess always merits attention: her Hotel Raphael is out in May (Picador), the same month as Andrew McMillan’s Pandemonium (Cape).

Debut novels dominated 2020’s Booker Prize shortlist, and there are several titles that are worth watching out for in the coming year. These include Megha Majumdar’s A Burning (Scribner January), a story of three intertwined lives set against the volatile backdrop of contemporary India, and Peace Adzo Medie’s His Only Wife (Oneworld, March) — both of which have already received rave reviews in the US.

Frederick Studemann is the FT’s literary editor; Laura Battle is the FT’s deputy books editor. Poetry selections by Maria Crawford

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café