The shroud of uncertainty surrounding further COVID-19 federal rescue aid has many public transit agencies and transportation advocates thinking worst-case scenario.

“Everything has to be on the table if we don’t get additional funding,” said Patrick Foye, chairman of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority. “Sadly, that includes the possibility of service reductions, which is absolutely the last thing we want to do. Layoffs would have to be on the table as well.”

Patrick Carey / MTA New York City Transit

Transit systems nationwide are seeking $32 billion to $36 billion from the U.S. Senate, which expects to reconvene within days. They received $25 billion under the CARES Act, which President Trump signed in late March.

Foye said the MTA will use the last installment of its CARES funding early next month.

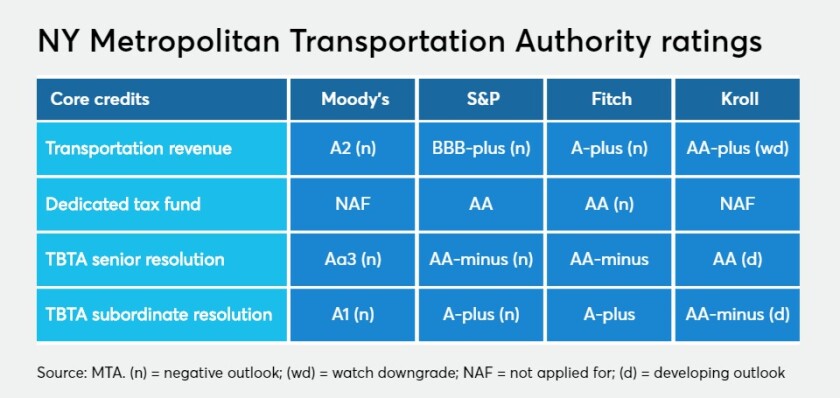

S&P Global Ratings, in its July 7 downgrade of the MTA’s primary transportation revenue bond credit to BBB-plus from A-minus, cited the “timing and amount” of additional federal aid, “if any.” The MTA has received multiple downgrades and warnings since the pandemic escalated.

The New York-based transit organization Riders Alliance took a more dramatic tack. In a nine-page commentary titled “Doomsday on the MTA,” it posed a scenario in which half the system’s subway trunk lines were eliminated.

“Agency leaders could face a ‘Sophie’s choice,’ eliminating every other subway line from New York’s iconic system map,” said Riders Alliance, which reproduced a barren-looking visual to drive home its point.

After the recession in the late 2000s, the MTA made $400 million in overall cuts. “In contrast, without the $3.9 billion it needs beginning in July, the MTA would now need to impose cuts totaling $650 million per month, or about 20 times deeper than the 2010 cuts,” Riders Alliance said.

In addition, congestion pricing for Manhattan’s central business district — designed to provide $15 billion of the MTA’s five-year, $51.5 billion capital program — is on hold for at least a year until the federal government can clarify the environmental process. Adding uncertainty, with so many office workers now working from home, there is less traffic to toll.

While the MTA is enduring what Foye called its worst crisis ever, bankruptcy is not an option. According to a recent official statement, state law specifically prohibits the authority and its affiliates from filing Chapter 9, and the state has covenanted not to change the law as long as transportation revenue bonds are outstanding.

Additionally, its transportation revenue bonds have a gross revenue pledge requiring payment of bondholders first.

“The MTA benefits from greater support from its sponsoring governments than typical U.S. transit agencies and has the highest strategic and economic importance among its peer group,” Fitch Ratings said.

Managing the unprecedented crisis has been a work in progress, according to the MTA’s chief operating officer, Mario Péloquin.

“One thing that we’ve learned with the coronavirus is that we’ve become managers of the unknown,” Péloquin said on a webcast sponsored by infrastructure firm HNTB and New York University’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

Throughout the Northeast, the pandemic has sent states and public transit systems scurrying.

In Massachusetts, a $17 billion transportation bond bill is headed for a conference committee amid some complaints that it doesn’t go far enough to benefit mass transit.

The state Senate approved it by a 36-4 vote along party lines Thursday, with Democrats in the majority. The bill would fund work on roads, bridges and transit, and earmarks $50 million for an east-west rail line between Springfield and Boston.

Leaders in the Senate and the House of Representatives, which approved their own bill in March before the pandemic took hold, will work out a final package. In general, the Senate version would not generate new tax revenues.

The civic organization Transportation for Massachusetts wants financial stability for regional transit authorities statewide and updated regulations and fees on ride-share companies such as Uber and Lyft, said its director, Chris Dempsey.

“Today’s Senate debate is a missed opportunity for senators to advance policies that would improve commutes, reduce tailpipe emissions, address embedded inequities and fix a woefully inadequate transportation system,” Dempsey said. “If today’s vote is all the legislature does this session it will mostly be a continuation of the status quo. We’re hopeful that the final bill that emerges from the conference committee will be more bold.”

Dempsey said the state-run Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority should be more out front in the push for federal funds.

“We’re the fourth or sixth-largest transit system in the country, depending upon what metric you use, and the MBTA not playing more of a leadership role leaves us a little bit of an outlier,” Dempsey said. “This is a function of the state political dynamic.”

A shortage of federal funding, Dempsey added, could force Republican Gov. Charlie Baker to provide more state money for the system, possibly explaining his low profile.

All the while, transit systems have taken note of changing commuter patterns linked to the work-at-home dynamic that mushroomed during the pandemic.

The Port Authority-Trans Hudson commuter rail system has noticed a shift in peak ridership for its trains between New Jersey and Manhattan, according to General Manager Clarelle DeGraffe.

“We have to be nimble because things are changing every day, every week,” she said. The early-morning commuters are primarily construction workers and other essential employees, while “office workers are coming back in dribs and drabs.”

A big intangible looms, DeGraffe added.

“We’re managing fear, and that’s a very different fear to get your arms around,” she said.

Mitchell Moss, director of NYU’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management, said transit systems must overcome perceptions of virus spread.

“It’s not mass transit, it’s sustained contact that has allowed the virus to spread,” Moss said, citing the rise in cases in smaller communities nationwide, and from gatherings such as weddings and funerals.

Some infrastructure projects, meanwhile, have advanced during the pandemic.

The MTA finished the repair of its L train Canarsie Tunnel connecting Lower Manhattan with Brooklyn while in New Jersey, Federal Transit Administration officials agreed to expedite the funding process to replace the 110-year-old Portal Bridge over the Hackensack River in Kearny, an important piece of Amtrak’s northeast corridor travel.

New Jersey Transit, which has been trying to catch up in its state-of-good-repair backlog the last couple of years, has asked for $1.2 billion in the next federal package, according to Chief Executive Kevin Corbett.

“If we backslide, the impact lasts for years and that’s why it’s so important that we get this additional funding,” Corbett said. “I think all the transit agencies are going to have to look at very tough situations of what we would do. The timing of that, it’s too early to say, but certainly we have a fiduciary responsibility ultimately, both for taxpayers and [bondholders].”

One positive is that agency heads have noted that a vast majority of transit riders are wearing face coverings.

“They had the tar scared out of them in New Jersey,” Corbett said.

Unknowns hold sway, said Leslie Richards, general manager of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, which operates mass transit in the Philadelphia region.

“This is going to last for some time now, months and months ahead,” she said. “This is not something that we can fix and return to normal.

“We have to keeping reminding people that they’re tired of dealing with the virus, but the virus is not tired of dealing with us.”