(This story is part of the Weekend Brief edition of the Evening Brief newsletter. To sign up for CNBC’s Evening Brief, click here.)

The addictive nature of video games, designed to keep players in the game for as long as possible, may make investors happy, but some are now warning that a regulatory crackdown could be coming for the industry.

In a new research report, Jefferies said that a growing emphasis on the side effects from hours spent gaming — fueled by design features that encourage users to stay in the game — could lead to increased oversight and headwinds for gaming companies.

“We see addiction and possible related regulatory, litigation or taxation consequences for the video game sector as a ‘black swan’ – largely not discussed or discounted,” Jefferies analyst Simon Powell said.

But not everyone sees it that way.

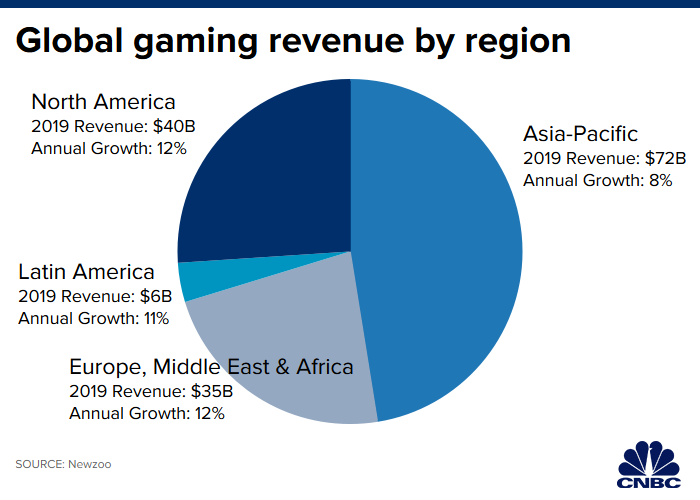

Strategic Wealth Partners’ president and CEO Mark Tepper said that while regulation could be a headwind for Chinese publishers, United States-based developers are relatively immune. For instance, he said that Activision Blizzard, which he owns, only has 13% exposure to Asia and that most of it is through the game Candy Crush.

When it comes to regulation in the U.S., which some have called for, Cerity Partners’ Jim Lebenthal said he isn’t worried. The difficulty in defining what exactly “addiction” means, coupled with Congress having “bigger things to tackle,” means he continues to own shares of Electronic Arts.

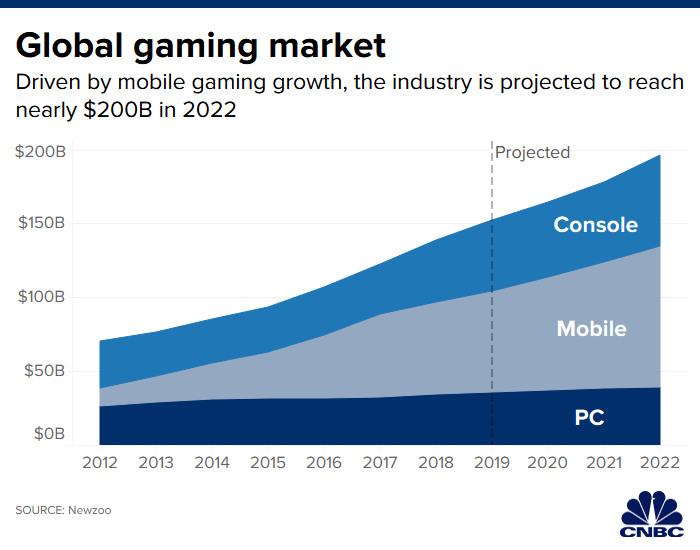

The video game industry has an estimated 2.5 billion active players worldwide, with mobile accounting for nearly 50% of the market. The industry is now worth $150 billion, according to Newzoo, which Jefferies noted makes it larger than the global box office and digital music industries — combined.

But video games have not been immune to the sharper eye society is now turning toward the impact of technology on peoples’ lives and the behavior some say it encourages, especially in the young.

In 2018, the World Health Organization officially recognized gaming disorder, which it defines as “a pattern of gaming behavior … characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences.”

Jefferies looked at aspects of the industry that could potentially be regulated, such as age and in-game spending, and then analyzed the impact on revenue. Overall, the analysts led by Simon Powell said that the industry is complacent, with an “apparent lack of concern” regarding the potential threat of regulation.

Calls for regulation are still in nascent stages in part because of the highly subjective nature of terms like “addiction” and “harm.” And not everyone agrees with the World Health Organization’s warning. The Entertainment Software Association in the U.S. and the Association for UK Interactive Entertainment, for example, are two organizations that have opposed the classification. Jefferies was also quick to note that there can certainly be a healthy amount of gaming, and that the addiction issue might lie more with the outliers.

But while investors are well aware of and focused on regulation when it comes to big tech like the “FAANG” names, Jefferies said that the Street isn’t applying the same sort of concern to video gaming stocks. “These issues aren’t front of mind or priced-in for some stocks … [we] don’t believe that these issues are at all high on investors’ list of priorities or concerns for video games stocks.”

Video game business model

Mobile and web-based gaming has revolutionized the way video games make money. These games are virtually all free to download, so companies rely on in-app purchases and to a lesser extent advertising to generate revenue.

In-game purchases can take on different forms. There are straightforward transactions where players buy something outright, such as ad-free play, and then there are also “loot boxes,” which is essentially when players gamble on something without knowing what they will get or the odds of getting it. Both purchases can be completed with dollars or in-app currency.

Jefferies said that this new games-as-a-service business has allowed the video game companies to thrive since the games can absorb large amounts of time and money without the risky hit or miss nature of prior video game launches.

But the overall revenue statistics might not tell the whole story. Gaming companies don’t typically reveal how much money the average player spends, which means that if a minority of players are spending the most money, any regulation of these high-dollar players could have an outsized impact.

“In mobile, it’s the minority who pay who support the whole industry – and thus if some of the highest spenders (logically including those addicted and harming themselves mentally or financially) were regulated to limit or remove their spend, the industry as a whole would be severely impacted,” the firm said.

The video game companies are known for collecting data on player behavior to tailor each user’s experience, Jefferies said, which means that investors could conceivably start asking creators to be more upfront and provide granular metrics on things like revenue per player.

Drawing in users

As is the case with other forms of entertainment — like movies, television, or music — where the aim is to keep people watching or listening for the longest amount of time, video game creators want to keep users playing.

The designers have used a combination of psychological and technological elements to maximize players’ experience, Jefferies said.

“Persuasive design is the practice of combining a psychology and technology to change people’s behavior. It is increasingly employed by video games and social media companies to pull users onto their sites and keep them there for as long as possible — as this drives revenue.”

The firm said that mobile games are the most at risk since it’s difficult to claim that features aren’t designed to keep users playing and spending money. Older, single-player games, by contrast, are physically purchased, meaning that the developer collects some revenue on that game regardless of how long is actually spent playing.

One of the reasons investors have piled into video game stocks is that they are seen as high-growth names, so any crackdown that prohibits users from playing freely could lead to a sentiment shift.

“At a high level, an industry generally seen as facing high growth and low risks would be derated if the growth, risks or costs of compliance were seen to be escalating unexpectedly,” the firm said.

When it comes to regulatory risk, not all games are created equal. Larger companies could have a better chance at surviving an increase in regulation, the firm said, since they are better positioned to handle things like costs associated with operations and litigation. More tightly regulated industries can also create higher barriers of entry, which can once again act as an advantage for larger companies.

Regulation around the corner?

The question of how to regulate the industry is challenging since it comes down to subjective interpretations of “addiction,” “excessive,” and a host of other terms.

But countries such as China and Korea already have game permitting systems in place. Jefferies said that there are many elements that could potentially be regulated, and that the industry, which has so far enjoyed tax breaks, could start to be taxed like other “addictive” past-times such as smoking, gambling or drinking.

“Regulations could come in multiple forms — limiting content, increasing scrutiny of permissions, enforcing (currently very lax) age regulations, limiting play time or spending (especially for children), regulating or banning certain games, mechanics, or features (loot boxes, which closely relate to gambling, have been regulated or banned as such in some markets and this trend is likely to spread),” the firm said.

Powell said that while investors might be aware of the regulatory hurdles in China, for instance, they are not pricing in risk from developed markets.

But Mark Tepper, president and CEO at Strategic Wealth Partners, said that it would be hard to enact similar legislation in the United States.

“The US has never taken steps to the extent China has when it comes to censoring, blocking, and regulating forms of entertainment like TV, movies, social media and video games. This isn’t something to worry about when looking at Activision Blizzard, Electronic Arts, Take-Two, etc.,” he said to CNBC.

He added that US publishers have minimal exposure to Asia, and also that they are partnering with Asia-based companies as a strategic and lower-risk way to enter foreign markets.

“Some could argue that it [gaming disorder] may limit future penetration into China (largest gaming market), but we still see positive trends from ATVI — partnering with Tencent to launch Call of Duty mobile in China gives good initial exposure to the market. And globalization of e-sports and team-based games (primarily Blizzard titles) are helping to connect ATVI to the Chinese gaming market,” Tepper said. He owns shares of Activision Blizzard.

What’s next from Washington?

In July, Senator Josh Hawley introduced the “Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology Act” or “SMART” act, which would ban features on tech platforms that are designed to be addictive, among other things.

On multiple occasions, the Oval Office has raised concerns about video games specifically. In 2018, President Donald Trump hosted a White House roundtable with video game company CEOs and representatives to discuss “the violent video game exposure and the correlation to aggression and desensitization in children” following the mass shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. In August, Trump again spoke of a possible connection between violence in video games and mass shootings.

But thus far there haven’t been any huge regulatory pushes. And Cerity Partners’ Jim Lebenthal, who owns shares of Electronic Arts, doesn’t anticipate any addiction-related legislation getting off the ground in the United States.

“I’m not worried about this at all, for many reasons. First off, Congress has a lot bigger things to tackle than legislating electronic games … I can’t see this making it onto the agenda anytime soon,” he said.

And even if addiction-related legislation were to advance, he said that other industries, such as casinos, would have much more to worry about. “Persuasive design is not illegal at all, at least right now. Someone may make it illegal, but there are other industries that have a lot more to lose,” he said.

Powell’s colleague in the United States, Alex Giaimo, echoed this point, saying that the U.S. government currently has “bigger fish to fry” and that he doesn’t see “a near-term scenario in which attention shifts to the Video Game industry.”

But the firm also said that government agencies aren’t the only ones who might get involved, and that the potential for future lawsuits related to addiction could cost the industry as much as $115 billion.

Ultimately, Jefferies said that investors “should be alert to potential changes on the horizon.”

Giaimo covers the U.S.-based publishers for Jefferies. He has a buy rating on Activision Blizzard, and hold ratings on Electronic Arts and Take-Two Interactive.

– CNBC’s Michael Bloom contributed reporting.