Business groups and opposition politicians have this week strongly criticised Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon over coronavirus lockdown easing plans that are markedly more cautious than those unveiled by UK prime minister Boris Johnson for England.

But comparative data through the winter wave of the pandemic suggest that Sturgeon’s greater willingness to maintain restrictions has helped Scotland keep deaths and infections lower than has been the case in England.

While deaths per million people in Scotland attributed to coronavirus exceeded those in England for more than a month in October and November last year, they went on to peak at a lower level. Excess deaths, seen as the best measure of the pandemic’s overall impact, have since December also been lower in Scotland.

The relative effectiveness of policy in Scotland and England has political implications: polling experts said the widespread perception that Sturgeon had handled the pandemic better than Johnson helped boost support for Scottish independence.

Linda Bauld, professor of public health at Edinburgh university, said Scotland had been helped during the winter by its success in achieving very low levels of infection last summer and by the fact that it had more warning of the more transmissible B.1.1.7 virus variant first recorded in Kent in September.

But Bauld said an important factor had been the Scottish government’s decision to tighten controls on interaction more quickly in the densely populated “central belt” that includes Edinburgh and Glasgow when new infections started to rise in September.

“Restrictions were applied . . . when cases were high but they were not as high as some of the levels you got in England,” she said. “Most of the central belt was living with pretty significant restrictions throughout November.”

As well as tighter controls under its tiered “levels” system for different areas, the devolved Scottish government imposed a nationwide ban on household visits in September at a time when Johnson was still resisting such a measure in England.

Mark Woolhouse, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at Edinburgh university, said acting earlier in the epidemic’s curve had led to a lower peak than in England even without a full autumn lockdown.

“That’s the general principle: the earlier you act, then usually the less draconian your actions have to be,” Woolhouse said.

Despite differences of population density, distribution and general health, the overall similarity of Scotland and England make them potentially useful for comparing the effects on the pandemic of different policy choices.

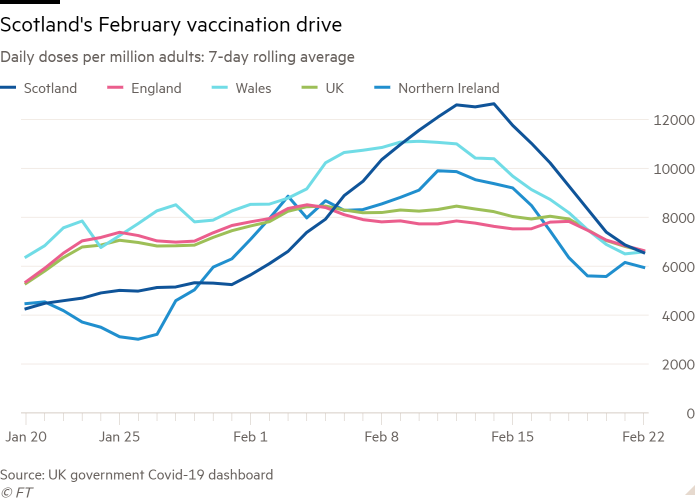

Sturgeon’s Scottish National party government was this month strongly criticised by opposition parties over a relatively slow rollout of the vaccination programme. The first minister insisted this was the result of a decision to focus resources on inoculating elderly residents of care homes, rather than ramping up jabs for over-80s in the community.

Excess deaths in Scottish care homes have fallen much faster in the past few weeks than in England, and the National Records of Scotland said on Wednesday that care home deaths in which coronavirus was a factor had plunged 69 per cent over the past four weeks.

Bauld said the Scottish approach reflected estimates that one life would be saved by 20 vaccines administered in a care home for the elderly compared with 160 needed to save a life among over-80s in the community. “I think that’s probably paying dividends now,” she said.

Scotland was able to increase vaccinations in the wider community this month to a rate above that of other UK nations and has now proportionately caught up with England.

Scotland’s approach to exiting lockdown remains fiercely contested, however, with the opposition Scottish Conservative party this week criticising Sturgeon for failing to set target dates for an end to social distancing of the sort announced by Johnson for England.

The Scottish Chambers of Commerce business lobby group said failure to keep “closely in step” with other nations of the UK would put Scotland at a “competitive disadvantage”.

Woolhouse said that in discussions of lockdown policy across the UK, there had been a lack of emphasis on and research into the huge health and social costs of maintaining restrictions.

Policies that halved the number of new coronavirus cases every two weeks by the nature of exponential decay brought diminishing returns that might soon be outweighed by the damage they caused, Woolhouse said.

“We need to make that reappraisal literally every fortnight — is it still worth it, in terms of the balance of harms?” he said.

But Devi Sridhar, professor of global public health at Edinburgh university, said Scotland should continue to aim to achieve maximum suppression of coronavirus rather than merely reducing infections to levels that do not threaten to overwhelm the health system.

Uncertainty about the effectiveness of vaccines in stopping transmission and the possibility that new, vaccine-resistant variants would emerge meant any other approach risked more lockdowns later, Sridhar said, adding that Sturgeon was right to be cautious.

“I think it’s better to under-promise and over-deliver,” she said. “We don’t want to have people dying who would be vaccinated in the course of the next few weeks.”