As Robert Smith laboured under a criminal tax investigation in recent years, the billionaire private equity executive played hardball with the Internal Revenue Service.

Mr Smith, the founder of Vista Equity Partners, had hidden $200m from the taxman offshore and evaded some $43m in taxes from 2005 to 2014, he admitted in a settlement this week.

But between 2017 and 2019, Mr Smith filed claims for $182m in tax refunds from the IRS — all linked to the same unpaid tax for which he was facing criminal charges.

The manoeuvres were revealed on Thursday as the Department of Justice announced that Mr Smith, who is the richest black American with a net worth estimated at $5bn, would pay $140m but avoid indictment for what he admitted was years of wilful tax evasion.

“You could look at it as chutzpah, or you could look at it as a proactive defence strategy,” Matthew Mueller, a former DoJ tax prosecutor now in private practice at Wiand Guerra King, said of the claims filed by Mr Smith.

He noted that one of the factors prosecutors weigh in bringing criminal tax evasion cases is whether they can prove that the target owes the government money. Tax refund claims in excess of any liabilities can be a useful defence.

Mr Smith gave up the claims as part of his deal with the DoJ that also requires him to co-operate. “He may actually be entitled to make those deductions, but clearly it was worth it to walk away from them to avoid prosecution,” said Mr Mueller.

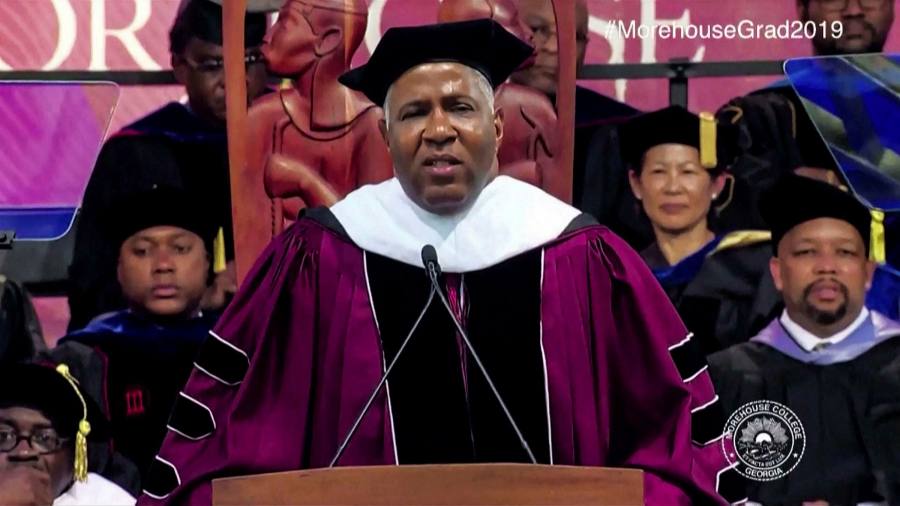

The 57-year-old private equity executive had become well known for his philanthropy and business acumen. Mr Smith made headlines in 2019 when he pledged to pay off the loans of students graduating that year from Morehouse College, a historically black men’s college in Georgia.

In April, he was among a list of “esteemed executives” announced by the White House who would help the administration revive the American economy from the damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

He is yet to comment publicly on the case, but told investors in a letter on Thursday: “I should never have put myself in this situation.” Mr Smith apologised to the investors “for any issues or concerns this may have caused for you”.

“I am relieved that this has been fully resolved and is now behind me,” he added. A spokesman for Mr Smith and Vista Equity declined to comment.

The announcement of his non-prosecution agreement on Thursday came as prosecutors brought tax charges against Robert Brockman, a Houston billionaire whose money launched Mr Smith’s private equity career in 2000. Mr Brockman denies the charges against him

As prosecutors indicted Mr Brockman in a $2bn personal tax evasion case that is the largest of its kind in US history, they said that Mr Smith would face no charges for his scheme to evade taxes by hiding some of his Vista Equity profits offshore. In return, he had agreed to continue co-operating.

“He got a great deal,” said Scott Schumacher, a professor at the University of Washington Law School and criminal tax expert. He noted that the government typically rewarded cooperators with their own criminal exposure by promising to seek leniency at sentencing, calling Mr Smith’s settlement “unusual to say the least”.

Mr Smith’s deal contrasted with the treatment of Ty Warner, the toys entrepreneur who created Beanie Babies, who pleaded guilty to a criminal charge in 2013 for evading $5.6m in federal taxes by stashing millions of dollars of income offshore. He paid $80m in penalties.

When the judge in Mr Warner’s case sentenced him to probation, the justice department appealed, arguing that “many individuals who have evaded far less tax have been sent to prison for their crimes”.

Just last week, the DoJ indicted the owners of three Dippin Donuts stores in New York state for allegedly evading $1m in taxes.

On Thursday, David Anderson, the San Francisco US attorney, insisted that Mr Smith’s deal had resulted from his co-operation with the government.

“This non-prosecution agreement underscores the importance of co-operation with a federal criminal investigation. That’s the message that we intend to send,” he said.

Richard Zuckerman, the head of the justice department’s tax division, was absent from the press conference. A spokeswoman for the division, which played a key role in the investigation of Mr Smith, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Mr Smith’s tax evasion scheme stretched over 15 years and began with the founding fund of Vista Equity in 2000.

Mr Brockman was the only investor in that first fund, providing $300m, according to the statement of facts in Mr Smith’s settlement.

As a result, one half of Mr Smith’s carry was in his own name and the rest was in the name of a Nevis LLC called Flash Holdings, which was owned via bearer shares by a Belize foundation called Excelsior.

Mr Smith secretly controlled both entities via a Houston lawyer recommended by Mr Brockman, according to the statement of facts.

The settlement document said Mr Smith paid the lawyer about $800,000 from 2000 through to 2014 for services including “assistance with the creation of a false paper trail, regarding the maintenance and operation of Excelsior and its related entities”, according to the statement of facts.

In his letter to investors on Thursday, Mr Smith said: “The decision made twenty years ago has regrettably led to this turmoil, which has put undue stress and burden on too many.”

Mr Brockman has pleaded not guilty to the charges against him.

Mr Smith used some of the untaxed funds on properties for his personal use in the US and France, and at times to fund his US charitable activities, he admitted in the settlement.

The scheme began to unravel in late 2013 and early 2014, when a Swiss bank Mr Smith had used, Banque Bonhôte, told him it intended to participate in a leniency programme that required it to tell the US government about any US citizens who banked with it.

Bonhôte advised him to seek leniency with the IRS under a voluntary disclosure programme at the time for Americans with hidden offshore accounts. Mr Smith applied and was rebuffed.

The IRS typically rejects applicants if it is already aware of their offshore accounts.

In December 2014, Mr Smith donated all the income he had accumulated offshore, some $200m, to a charitable foundation he runs, the Fund II Foundation. The following May, he tried to seek leniency from the IRS again.

He filed amended foreign bank account reports and tax returns with the IRS through a different programme that allows taxpayers to correct failures to report foreign assets by attesting that any mistakes were accidental and paying a 5 per cent penalty.

Mr Smith admitted in the settlement that these amended filings were also “wilfully” false. He claimed only signing authority over his foreign bank accounts, rather than disclosing he was the true beneficiary, and did not report the $200m of offshore partnership income despite knowing it was taxable.

The settlement documents show that in 2017, Mr Smith filed a protective claim with the IRS for a refund on the money he paid when he filed the amended but still false tax returns and foreign bank account filings in 2015.

In 2018 and 2019, he filed protective claims for charitable deduction refunds for donating his hidden assets to his foundation in 2014.

A person familiar with the matter said Mr Smith had made the claims “at the advice of counsel to protect any claims he may ultimately have, before any determination was made as to whether the assets belonged to him”.

Mr Smith’s deal with the justice department requires him to pay $139m in back taxes and penalties. Half was due immediately, with the rest paid in quarterly instalments over 18 months.