Did Arsène Wenger get the balance right between being a football manager and being a person? “I got it completely wrong,” he laughs. “I would not advise anybody to lead the same life. Sometimes I think what kind of human being I might be, because to be obsessed like that and sacrifice everything — I was not completely normal. It was a completely unbalanced life.”

Wenger, 70, hasn’t yet mastered the trick of putting his laptop on a pile of books, so his familiar aquiline features peer down on me from Zoom. He has kept quiet since his ousting as Arsenal manager in 2018, after 22 years in the job. Now he is unleashed. His new memoir, My Life in Red and White, takes us from his childhood in the Alsatian village of Duttlenheim to his current estrangement from Arsenal — a lifetime spent thinking about football, management and what it takes out of you.

Duttlenheim made Wenger. He was raised there only a few years after the village’s return to France. Hitler had annexed the perennially contested Alsace in 1940, and the men of Duttlenheim had been conscripted into his army. Wenger’s book glosses over the topic in less than a paragraph but when I ask about it, he answers.

“My father did fight for the Germans on the Russian front. My mother told me [that] when he came back, he was 42kg . . . between life and death, [he] was in hospital for months.” How did the war’s legacy affect Wenger, the youngest of three children? “In my family, we didn’t speak a lot about the war. It was like a banned subject. I was not educated in that environment at all.”

His parents ran the village bistro, La Croix d’Or, while his workaholic father also had an auto-parts business. They had worked nonstop since they were 14. “We were a family without my having any understanding of what that word meant,” Wenger writes. “We never ate together and we talked very little.” There were no books at home in the rue du Général de Gaulle.

He grew up in the bistro, among adults, watching the local farmers argue, laugh, lie, get drunk and sometimes brawl. Duttlenheimers at the time still spoke the Alsatian German dialect. Wenger learnt French at school. The main topic of bistro conversation was football, especially on Wednesday evenings, when the village club held its selection meetings.

Wenger muses about his life choice: “Is it the fact that I grew up only in a football environment? As a young kid, I was just listening and thinking, ‘That is the only thing that matters, basically, because people talk only about that.’”

Duttlenheim also connected him with Germany. He didn’t inherit any hatred. “I was curious to see why should people be different on the other side of the Rhine. On top of that, on the football front, they were quite good at the time, the Germans, better than the French.”

He rose to become a journeyman player, usually a reserve, with Alsace’s biggest club, Racing Strasbourg. All through his career he was hampered by his poor technique, acquired on Duttlenheim’s bumpy village ground without a trainer. Perhaps that was what inspired his choice of vocation. In 1974, he graduated in economics from Strasbourg University, but he was always going to be a coach. He’d drive to Germany to watch matches from the warm-up onwards, sometimes getting home at 5am.

For a man from a backwater, the connection with Europe’s strongest football country provided life-long learning. In 2008, I hosted a discussion between Wenger and Bayern Munich’s then manager Ottmar Hitzfeld at a sponsors’ evening in Switzerland. During each break, Wenger pumped Hitzfeld for information in near-perfect German. How many kilometres did Bayern’s central midfielders run per game? How physically strong was Bayern’s winger Franck Ribéry? (He once deposited a 100kg club doctor in a washbasin for a lark, replied Hitzfeld.) At press conferences, Wenger could look tense, upright and grim but among football men in their natural habitat — five-star-hotel bars — he switched on his bistro skills of humour, storytelling and mimicry.

What did he take from German football? “I would say it shaped my career, the fact that the Germans had always a desire to play. It’s not, ‘Give the initiative to the opponent and only use the weakness of the opponent.’ They take initiative to express themselves as a team.” This became Wenger’s personal ideology: winning with style. He says: “The teams who remain in history are the teams who played with style. Football has to be transformed into art. The basic is winning, but you need a bigger ambition than that.”

Like many Alsatians, Wenger thought of himself as a European. Yearning to discover the world beyond Duttlenheim, he spent a month in Hungary in 1974 to see how a communist regime functioned. He recalls: “I came back during my football holidays and was convinced that they would collapse.” Four years after Hungary, aged 29, he went to Cambridge to learn the English he knew he would need in his coaching career. He recalls, “I worked hard those three weeks,” which, coming from him, is saying something.

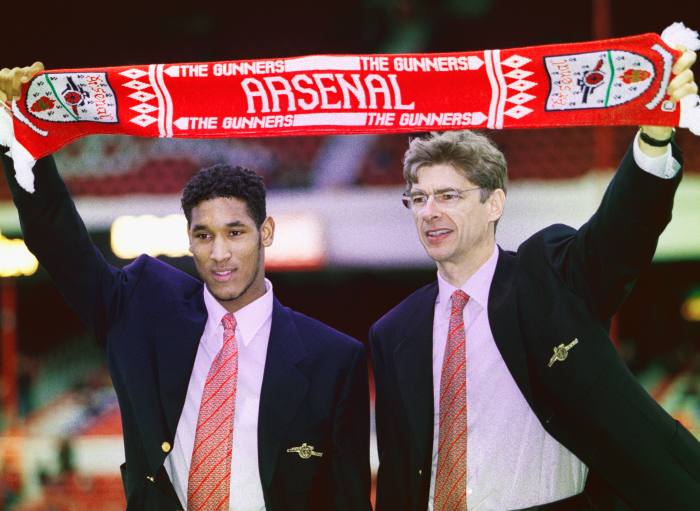

He worked hard at coaching too. At the French club Nancy, after losing a game just before Christmas, he managed to drag himself to his parents on Christmas Eve, but otherwise spent the three-week holiday break suffering alone at home. He made his name in seven years at Monaco. One New Year’s Day during his time there, he flew on a whim from Turkey (where he’d been watching football) to London to catch Arsenal vs Norwich. In the stands, he got a light for his cigarette from a woman who turned out to be friends with the wife of David Dein, Arsenal’s vice-chairman. That evening he was invited to the Deins’ home, where he impressed by acting out A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a game of charades. Wenger and Dein became friends, which meant they talked football. Wenger moved from Monaco to a job in Japan, and one day in 1996 an Arsenal delegation flew in to ask him to become the fourth foreign manager in the history of top-flight English football.

Wenger landed in the insular English game like a visitor from the future. He became one of the great ideas-spreaders who have shaped European football, in the tradition of Béla Guttmann, Johan Cruyff, Arrigo Sacchi and, later, Pep Guardiola and Jürgen Klopp. He understood nutrition, was already using statistics to evaluate players and, above all, he knew the foreign transfer market. He rescued the young Frenchmen Patrick Vieira and Thierry Henry from the benches of Italian clubs and discovered the teenagers Nicolas Anelka and Cesc Fàbregas.

Wenger had the rare gift of making adult footballers better. He explains: “You have to develop the fundamental quality of each player. None of us has all the qualities, but you have one dominant quality and that can help us to make a life, earn a living.” Once he’d identified that quality in a player, he invested years in helping him develop it (not always successfully; some of his protégés had to be discarded when they couldn’t make the grade even after repeated chances in Arsenal’s first team).

His great success story was the young Henry, a pretty but ineffectual winger. Wenger told him he was a striker. “Coach, I don’t score goals,” protested Henry. He became the highest scorer in Arsenal’s history. Wenger turned the French defender Emmanuel Petit into a World Cup-winning midfielder. He persuaded his hard-drinking English defenders that by changing their diets, they could play far into their thirties and with more style than they had ever imagined they had in them.

He tells me: “When you go up to the top, top level, it’s the individual player who makes the difference, who makes you win the game. We as managers take a lot of credit that maybe we do not always deserve.”

He believes that great footballers usually only reveal themselves around age 23. At that point, “the top, top, top players separate from the rest. These are the players who have something more, in the consistency of their motivation. And money has not too much [of] an influence on them. They have this intrinsic motivation that pushes them to get as far as they can. It’s not many of them.” These players, he observes in the book, are perennially dissatisfied with themselves and lead “difficult, unrewarding, monotonous lives … ruled by performance and repetitive daily rituals”.

If the best players are self-driven, then how much of the manager’s job is motivation? “It is overrated,” he replies. “If you have every week to motivate players to be performing on Saturday, forget it. If they don’t want it, leave them at home, you’ll waste your time. You’re not there to motivate players who don’t want it. Globally, players at that level are motivated.” He believes the manager’s task is to create a “performance culture” that pushes players to ask themselves “the fundamental questions: how can I get better? Have I achieved my full potential? What can I do to get there?”

How much do players even care who the manager is? “Everybody finds in the manager the quality he wants. Sometimes it’s communications, sometimes it’s more a technical aspect, sometimes a more tactical aspect.”

Wenger lived 22 years in London, but felt as if he “lived in Arsenal” instead. He writes: “The idea of taking holidays, having a good time, never occurred to me, or hardly ever.” He’d rise at 5.30am, spend days at the training ground and evenings imbibing televised matches from around the world in his modest suburban house. When his only child Léa was born in 1997, he admits: “I was probably too busy with my work to realise that this was a blessing.” He now says he has regrets, but he never considered putting football second.

His Arsenal won three English league titles in his first eight seasons, including two league-and-cup Doubles. In 2004 his “Invincibles” became champions undefeated, playing some of the most brilliant attacking football ever seen in England to that point. That season, he was probably the most feted manager in the game. But it turned out to be the last league title he ever won.

In the book he inveighs against the “winning at all costs” attitude. Hang on, I say, he often looked like a winning-at-all-costs guy, lambasting referees and once reportedly grappling in the players’ tunnel with his arch-rival and soulmate, Manchester United’s Alex Ferguson. “It’s true,” he allows. “It’s a contradiction that I have in myself: I was a very bad loser.”

The hardest defeat was the Champions League final against Barcelona in Paris in 2006. His goalkeeper Jens Lehmann was sent off early, but late in the second half Arsenal were leading 1-0. Then Henry missed a one-on-one against the goalkeeper and Barça scored twice.

Wenger reflects: “With 13 minutes to go, we were on top of it. Maybe I could have played with three centre-backs in the end and hope that we get away with it. I thought it very unfair and frustrating. You know, when we won 5-0 or 7-0 I went back home and I thought, ‘What kind of mistake did I make?’ When I lost 2-1 in the Champions League final, of course I go home and think, ‘What could I have done differently?’” He hasn’t been able to watch the game again.

In 2007, I sat a row in front of him in the stands in Athens watching the Milan-Liverpool final. While Milan’s players collected their winners’ medals, Wenger thumped his hands together grimly and exclaimed, “You see, you only need an ordinary team to win the Champions League.” A keen mathematician, he understood that success in a knockout competition is largely a random walk. He never got lucky.

His reign at Arsenal petered out. Did he get left behind, as pioneers do, once other clubs discovered data, nutrition and the international transfer market? He laughs angrily: “We live in a job where you’re always judged to be a winner or not. But I think what happened is financially we built the stadium and we had less resources.”

The Emirates Stadium is Wenger’s most tangible legacy, not just to Arsenal but to London. He redrew the map of the city. The Emirates’ capacity of 60,000 is 22,000 more than Arsenal’s old ground, Highbury. Arsenal have consistently filled it since the beginning, generating the largest average crowds in London’s football history, but they borrowed most of the £430m that the move cost and spent Wenger’s last decade in power repaying it.

Meanwhile, oil-rich owners like Roman Abramovich at Chelsea and Abu Dhabi’s ruling family at Manchester City poured money into Arsenal’s rivals. This stung Wenger: in a very French way, he found it unfair that money (“financial doping”, he called it) could win football matches. Arsenal could no longer afford the best players, especially given Wenger’s proclivity for austerity. (We spoke before this week’s proposal by Liverpool and Manchester United for Premier League clubs to bail out the lower divisions of English football, which have been stricken economically by the ban on spectators, in return for the big clubs taking more power.)

With hindsight, his grand plan didn’t work out: though the Emirates is now almost paid off, it hasn’t returned Arsenal to the top, partly because rival clubs have built new stadiums too.

Wenger took a lot of abuse during the downhill years. Fans would chant, “Spend some fucking money!” Yet he always felt he had the best job in football. Whereas higher-achieving peers such as José Mourinho were mere short-term contractors, responsible only for first-team results, the Alsatian was the last manager in Europe who ran a big club single-handedly. He made every major decision himself. It was intellectually thrilling. Even as a hard-pressed coach in his late sixties, he looked forty-something and had the energy of a 30-year-old.

But now he reflects: “The job like I did it, or Ferguson did it, has disappeared. Because the clubs’ structure has changed. Today, transfers are so big that negotiations are not any more in the hands of the manager or the coaches [but] in the hands of people who are specialised in that. So the structure has inflated. The human side is more difficult, you have more people to manage. The science has developed, the team around the manager has developed tremendously. He has problems to manage the egos not only inside the team but outside.”

He recalls that in his early years at Arsenal, board meetings were “quite democratic”, with debates between people who owned 15 or 20 per cent of the shares. In 2011, the American entrepreneur Stan Kroenke emerged as Arsenal’s majority shareholder. He has since bought full control. Today, observes Wenger, almost all big English clubs are foreign-owned. “In the vote England made for Brexit, I read personally a desire for people to gain back their sovereignty. But it’s funny because nobody spoke about football, which has lost completely sovereignty on its own decisions.”

Arsenal finally asked him to leave in May 2018. “I wasn’t ready to go,” he admits in the book. “Arsenal was a matter of life and death to me and, without it, there were some very lonely, very painful moments.” He has never been back to the Emirates to watch a game. He says: “Today I have no contact with any deciders in the club at all, so I feel maybe it’s better I continue like that.”

Is he hurt that Arsenal don’t seem to want him around? “Look, errrr, ‘hurt’. I built the training centre, I contributed highly to build the stadium and when you do that, you imagine you come back and live for ever at the club. But life is not like that. It’s a new era and maybe people feel comfortable when I’m not there.” The implication is that even his former player Mikel Arteta, now Arsenal’s manager, has not sought out his advice. Still, Wenger writes that under Arteta, “these values, this spirit, this style that was characteristic of the club can once again come to the fore”. This reads like a jab at Wenger’s immediate, shortlived successor Unai Emery.

Coronavirus permitting, Wenger now moves between London, Paris and Zurich, where he works as Fifa’s head of global football development, charged with spreading good coaching worldwide. Many children in Africa and elsewhere still grow up uncoached, as he did in Duttlenheim.

Is it hard to cope with civilian life after decades of big-match adrenaline? “Yes it is. The boring side of daily life is not exciting for anybody. I still miss the intensity of the weekends. My life was on grass. On the other side, I think, ‘Look, I’ve given enough.’”

He still wakes at 5.30am and checks that evening’s match schedule before putting in his ritual 90 minutes in the gym. But he spends more time now with friends and with his daughter, who is finishing her doctorate in neuroscience at Cambridge. He watches films and reads. “At the moment I’m finishing Sapiens [by Yuval Noah Harari]. I read more articles than books, specialised articles on managing people, on motivation, on team spirit.” He gives talks on management at business conferences. Above all, he continues his life-long study of football.

“In the last 10 years, the main evolution has been physical,” he diagnoses. “We have gone for real athletes and, from the day where everybody could measure the physical performance, all players who could not perform physically well were kicked out of the game.”

Isn’t that sad? A player as gifted as Arsenal’s Mesut Özil, signed by Wenger in 2013, has become unwanted because he cannot cope with today’s frenzied pressing game. “Yes, it has killed some artists,” agrees Wenger. “Today, football goes at 200 miles an hour, so you have to show first that you can go on the train. Once you’re on the train, you can express your talent but if you cannot get on the train, you don’t play.”

“I think it has uniformised a bit too much the way to play. Today you have two kinds of play. Teams defend very high [near the opponents’ goal], or very deep [near their own goal]. Basically, the [manager’s] speech is always the same, ‘Let’s win the ball back as quickly as possible and try to kill on the break.’ Everybody presses on the first ball from the keeper. It has emphasised chain-defending to close balls down. And it has killed a little bit the creativity.”

He writes of rejecting “countless proposals” to return to management. Yet he hasn’t ruled it out, has he? He laughs at himself: “I’ve not enough courage at the moment to see that world is definitely over for me. So I leave a little bit my space open to not completely kill what I lived for.”

How does a workaholic deal with reaching his seventies? “You forget how old you are. There is only one solution, you will see that later: until the last day of your life, fight and forget about all the rest, do your job. Don’t think too much, because that doesn’t help. As long as we live, we have to do something. Love, create and work, and don’t consider too much the time that you have in front of you. Nobody knows.”

Does he feel 70? “Not at all. I still play football, official games. My next game is on November 9. I must say honestly, I cannot play every three days.”

Does he never think, “It’s only a game”? He laughs at himself again: “No. That is absolutely fascinating. Last night I watched Tottenham versus Chelsea in the Carabao Cup. I went to bed, I think, ‘I missed some things.’ It’s like I see the first game every time.”

Simon Kuper is an FT columnist.

‘Arsène Wenger: My Life in Red and White’ (W&N) is out now

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.