Reopening public schools for in-person instruction has proven highly complex and visceral for New York Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration.

Family emotions, union pushback, fears of a new COVID-19 wave, cost drivers and data fluctuations are all at play.

Bloomberg News

Multiple references to “Rubik’s cube” and “whiplash” dotted Mayor Bill de Blasio’s press briefing Thursday about the most recent pivot, an 11th-hour move to a staggered reopening by grades, and the hiring of 2,500 more new teachers.

The announcement came four days before schools were to have opened in person, leaving parents across the city in the lurch with little time to make alternate child-care arrangements.

“You have parents wondering about their children — there’s that issue — and then you have a pretty powerful [teachers] union,” said Howard Cure, director of municipal bond research for Evercore Wealth Management. “Add on that for a lot of parents, school serves as child care. So you have all three adding up to a pretty controversial situation.

“We’ll see if it works. It sounds nice, but it’s dangerous.”

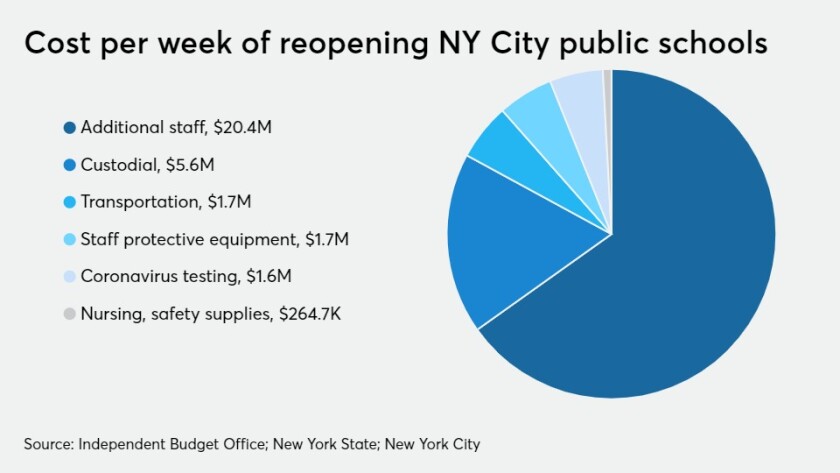

It’s also costly. The watchdog Independent Budget Office estimated a $32 million additional weekly cost of operating the schools in-person across multiple city agencies while complying with state public health guidance. That preceded de Blasio’s announcement of the new teachers, bringing the total of related teaching-related hires to 4,500.

The additional hires seemed to placate the teachers union.

“The plan that we all agreed upon is the right plan. It is the most aggressive with the greatest number of safeguards” said United Federation of Teachers president Michael Mulgrew, who appeared with de Blasio at his daily news briefing in the City Hall Blue Room. “That also means it is highly complex, to say the least.”

Earlier in the week, an activist wing of the UFT, whose workforce returned to class Sept. 8 to prep for the opening, staged a “work-out” at several schools, fulfilling duties outdoors while arguing that many school buildings are still unsafe.

The city intends to operate under a blended learning system that will combine in-class and online learning. Under the phased-in plan, pre-kindergarten, 3-K and special-education students will return on Monday, while K-through-5 and K-through-8 students will go back on Sept. 29. Middle- and high-school students will go in starting Oct. 5.

The nation’s other large urban school systems are beginning the year with online instruction but New York’s much lower coronavirus transmission rates at least appeared to open the door to in-person teaching. Statewide, new coronavirus cases are at about a quarter of the rate of the nation as a whole, according to data compiled by the state health department and the New York Times.

IBO’s estimate reflects personal protective equipment for students and staff, safety and medical supplies, and the additional costs of staffing, school bus transportation and monthly coronavirus testing, according to IBO director Ronnie Lowenstein.

While IBO made no assumptions about funding availability, some costs may qualify for federal reimbursement under either already-enacted relief legislation or any future bill, Lowenstein added.

“Aside from the operating costs we identified, there are also additional capital costs that will be incurred, such as costs for upgrading HVAC systems, purchasing air filters for classrooms, and purchasing additional tablets and hotspots to meet students’ technology needs,” she said in a letter to City Council member Mark Treyger.

IBO, Lowenstein said, has not gauged costs for these or other capital needs.

The city’s enacted school budget had been $34 billion for fiscal 2021. Of that, the city and state provide 57% and 36%, respectively, while the federal government and other sources cover 7%.

“We have existing resources that we’re applying to these additional — to the additional staffing and we’re making available an additional $50 million to make sure that this is completely accomplished and we’ll obviously find savings and we’ll reflect those in the future financial plans,” said First Deputy Mayor Dean Fuleihan, a former city budget director.

The city’s Department of Education has a separate capital budget of more than $17 billion to renovate schools, build new ones and purchase equipment over five years. The city’s School Construction Authority administers the capital budget.

Meanwhile, the Federal Emergency Management Agency said it would no longer approve reimbursements for deep cleaning of schools, mass transit, schools and other public facilities because they “are not immediate actions necessary to protect public health and safety.”

As of Wednesday, 55 city Department of Education personnel had tested positive for the virus among nearly 17,000 individuals tested.

Some educators had complained about out-of-position assignments, such as gym teachers instructing math. Cybersecurity is also a concern. One Brooklyn parent said her sixth-grade student encountered pornography during an online class.

“It’s never going to be perfect, but it will be what schools need. And this balance between the remote and the in-person, it’s complex, it’s unprecedented,” schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said. “We can’t be all things to all people. And I think there’s a healthy dose of realism that needs to be not only recognized but also talked about.”

Ray Domanico, director of education policy and senior fellow at the free-market leaning think tank Manhattan Institute, criticized the de Blasio administration.

“After spending the last two years pursuing a misguided and divisive approach to educational equity, New York City’s mayor and schools chancellor have failed in their most basic mission — to actually provide educational services to the schoolchildren in their care,” Domanico said.

Private, religious and charter schools and networks have delivered a “diverse and creative” set of approaches, according to Domanico.

“At the Department of Education, resignations at the highest level are in order. In Albany, the governor should find ways to prevent the current mayor from inflicting any more damage on the city in his final 15 months in office,” he said.

The state legislature granted the mayor control over its schools in 2002, when Michael Bloomberg was mayor, shifting oversight from 32 school boards. The state budget passed in April 2019 extended the agreement by another three years.

The reopening also weighs against a backdrop of the city’s overall management since the coronavirus escalated in March.

“Issues in the public eye — primarily the schools and public safety — are easy to cite as examples of ideology clouding management competence,” municipal bond analyst Joseph Krist said. “The ongoing debacle over the opening of schools just extends and complicates the economic recovery.”

While Moody’s Investors Service has called the school reopening a credit positive for the city in its comeback effort, it warned that any benefit could be short-lived if New York’s infection rates begin to rise again.

Tuesday’s disclosure that JPMorgan Chase & Co. sent several traders home when they tested positive for the virus reinforced the concerns about a widespread return to offices and schools in New York, plus the pending return of indoor dining.

Before the pandemic, the school system was under question for its space management, with some districts overcrowded.

“Now you have to worry about overcrowding because of health concerns,” Cure said. Variables include possible spreading of the virus among children, teachers and parents who themselves work at service-related jobs with more exposure.

The oncoming traditional flu season adds a threat of a dual surge.

“The coronavirus is still very new in our lives. The flu has been around a long time,” de Blasio said. “Even though we’re used to the flu, we should not underestimate it. It can be deadly.”

Chris Low, chief economist for FHN Financial, warned against false confidence. “The aggregate trend looks good, but there are still plenty of problem areas that could turn the national trend upward again,” he said.

The watchdog Citizens Budget Commission last year recommended counter strategies to school crowding that could save $2.4 billion in the capital budget. They included rezoning districts, repurposing seats and enforcing high school enrollment caps.

“We keep building more schools and we’re still in the same crowded state that we’ve been for 20 years,” CBC President Andrew Rein said on a recent Volcker Alliance webcast. “Yes, we’re in a COVID era and space is a little different, but just generally, I think it provides the example of [alternatives].”